24, January 2019

La Republique’s plan for a Francophone-led tech hub isn’t being welcomed in Ambazonia 0

The Cameroon government is backing a new technology hub to be called “Cameroon Silicon River” in its capital city Yaoundé, in a move that is likely to move attention from its small, but already thriving ecosystem in the country’s southwest region.

The new tech hub is modeled after Buea’s Silicon Mountain and will take a sizable portion of the 11.92 billion CFA francs ($ 20.6 million) 2019 budget of Cameroon’s ministry of scientific research and innovation. The government says Cameroon Silicon River will be a platform for research and innovation where young, creative, and enterprising Cameroonian software developers and other technologists will have the infrastructure and support they need.

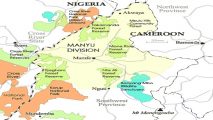

But the news has not gone down well with tech leaders and entrepreneurs in Silicon Mountain; the already burgeoning tech ecosystem in Buea, in the English-speaking region of Cameroon. It is seen as the latest part of a wider national effort to marginalize the minority English-speaking regions of the country in the southwest and northwest.

For the last two years activists in the English-speaking regions of the country have protested against marginalization by the French-speaking dominated government. Modern Cameroon was formed from part of a former British colony and a much larger French colony, which makes up about 80% of the country’s population. But over the last year, those initially peaceful protests by Anglophone professionals, including lawyers and teachers, have turned into violent clashes with government security forces.

There has also been an information battle conducted mainly online. The government has taken to shutting down the internet for months in the English-speaking regions, ostensibly to prevent anti-government activists organizing.

Tech entrepreneurs in Silicon Mountain have often complained of systematic neglect by the government, citing specifically the lack of tax incentives for their tech start-ups and want of financial support.

Despite the difficulties, some Cameroonian start-ups in Silicon Mountain have received global acclamation and are being scaled up to spread across the world. These include Zuo Bruno (Zuoix)’s Zoomed car-tracking application using SMS and Churchill Mambe Nanje’s Njorku.com – a fast-growing job search engine and aggregator that helps thousands of African job-seekers find employment opportunities in locations nearest to them.

Bruno, an ethical hacker from Silicon Mountain, described the Yaoundé hub plan as a waste of resources. “I think it is a decision that assumes creativity and innovation can be taught and politicized.”

Many techies in Silicon Mountain say government officials often speak with them on how to improve the local ecosystem but their suggestions or proposals often end up being implemented in other parts of the country.

“We had proposed to officials that there was need to put in place an institution in Buea that will help startups in registering their ventures and scaling them up. Now we hear it is Yaounde,” said Otto Akama, co-founder of Makonjo Media. He indicated that same had been done with the creation of a technopole in Kribi, in the country’s French-speaking region.

Internet rights activist, Gwain Colbert Fulai predicted Cameroon Silicon River will die off in a relatively short timeframe.

“When you copy an initiative, you miss out the essential details. Even Silicon Valley in the US was not a government creation,” Colbert said. He argued government should only create an enabling environment for technology to strive.

Despite being Cameroon’s capital city, Yaoundé has few little-known tech entrepreneurs compared with Silicon Mountain. The entrepreneurs believe government should use the striving Silicon Mountain tech ecosystem as a springboard to build and expand other ecosystems in the country.

Source: Quartz

24, January 2019

2019 AFCON Fiasco: Aecom’s ‘impossibly fast’ delivery of 50,000-seat Cameroon stadium 0

Cameroon may no longer be hosting the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations, but the Japoma Stadium is still set to be delivered to the original, tight schedule.

Project name: Japoma Stadium

Client: State of Cameroon

Value: $220m (£171m)

Contract type: Design and build

Main contractor: Yenigün

Design and structural engineer: Aecom

Steel subcontractor: BCES Bülbüloğlu

Façade subcontractor: Tensaform

Start date: January 2017

End date: March 2019

“By the time we had a deal and were able to start, we only had two years to deliver the stadium,” says Aecom director and head of sport Peter Ayres. The stadium in question is Cameroon’s Japoma Stadium, which is designed by Aecom and being delivered by Turkish contractor Yenigün.

“We had a very general idea conceptually of what we needed to build,” Mr Ayres says, “as in we need a 50,000-seat stadium and we’ve got a site […] but that was it. There was no design as of two years ago. Mr Ayres adds that, normally, it takes a minimum of three years (“absolute minimum”) to design and deliver these projects.

The new stadium was sanctioned alongside three others as Cameroon prepared to host the 2019 African Cup of Nations football tournament. But in November last year, the country was stripped of its right to host the event due to preparation delays and security concerns. Despite this, the time and cost-saving design and construction of the Japoma Stadium in the port city of Douala has meant the project has stayed on schedule. Given the hugely ambitious programme, it has been no mean feat.

Design based on speed and trust

Aecom was approached by the government of Cameroon at the start of 2016. Mr Ayres says the client wanted a turnkey package, which the firm was unable to provide. Instead, Aecom managed to put together a consortium with main contractor Yenigün, who also brought onboard a Turkish bank to part-fund the scheme. By the time all the deal-making had concluded, the contract was signed and the money started to flow through for construction, it was already January 2017. This is when the “nitty gritty designing” work actually kicked off, says Aecom associate director of building engineering Adrian Armstrong.

With the stadium needing to be handed over to the client in a little over 26 months by the end of March 2019, a time-efficient design and build process took priority. One of the first things this meant was, “there had to be an element of trust” on the client’s part, according to Mr Ayres, as there simply was no time to offer “27 different options” for the design. “It was [a case of], ‘This is what works, this is what can be built quickly’. We’ve got our site, how do we work with the site? Instead of trying to fight the topography, let’s work with it,” he says.

A stadium on a hillside

Douala is 200 km west of Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital. The site chosen for the stadium is less than 5 km west of the Dibamba River, which is forested on both banks. “When we got there, [the site] was all covered in bush. It was semi-forestry wasteland, but there were trees, ditches, bits of marshy areas that all had to be cleared and levelled,” Mr Ayres explains. The most intriguing element of the site however, is that it sits on a hillside. There is a 7 m difference in elevation between the lowest and highest points of the hill (pictured, below).

There is a 7 m difference in elevation between the lowest and highest points of the hill The Aecom team took advantage of this by placing all of the changing rooms, operations and internal accommodation facilities on the west side of the stadium, at the bottom of the hill. This meant excavation and earth works could be kept to a minimum, Mr Armstrong explains, as the basement level did not have to be dug up. Relative to the rest of the stadium, the basement sits on a lower floor, but because it has been positioned to sit at the bottom of the hill, it is still at ground level. Another benefit of building the stadium on a hill is that, “we can bring people in at halfway up the stadium bowl,” Mr Armstrong adds. “That means you don’t need lifts and staircases, because for three-quarters of the stadium, people come in and they either go down into the bowl or up into the bowl.”

Starting from the west

Piling work started on site in May 2017, five months after the starting pistol was fired on the scheme. Main contractor Yenigün’s in-house groundworks team installed a total of 2,076 bored piles, each 800 mm in dimeter. Depending on the level on the site and the ground conditions, the piles varied in length from 8 m to 20 m. Given that all of the additional elements in the stadium (basement, VIP box and premium concourse) were all centralised in the west stand, piling work started there. Time constraints meant that as soon as piling for the west stand was complete, Yenigün turned its attention to the stand’s substructure and superstructure, as piling work continued across the rest of the job. Yenigün used insitu concrete for the primary frame as well as for the 48 raker beams that form the stadium’s superstructure frame, which supports the seating terraces.

[BCES Bülbüloğlu] built the whole truss on the ground, lifted it in as one piece and placed it on the concrete structure The Turkish contractor set up a precast concrete batching plant onsite to produce a portion of the concrete required for the terraces, while the remainder was imported from Turkey. “Because it’s such a wide perimeter and we wanted to reduce the amount of insitu concrete for [the sake of] speed, we developed a system where the precast terracing units, which normally would be single 7.5 m spanning elements, we made them into double elements,” Mr Ayres explains. “So instead of being an ‘L’ shape, they’re ‘W’ shaped. That meant we could span twice as far, which meant we could halve the number of insitu units to speed up construction,” he adds.

Porous roof and façade

As this process fanned out across the circumference of the stadium and the 50,000-seat arena took shape, Turkish steel contractor BCES Bülbüloğlu began erection of the steel cantilevered roof. “We came up with 3D trusses that are self-stable,” Mr Armstrong says. “[BCES Bülbüloğlu] built the whole truss on the ground, lifted it in as one piece and placed it on the concrete structure.

Low maintenance design

In order to create a stadium that would fit the demanding programme, have a lasting legacy and be cheap to operate and maintain, the Aecom team made several forward-thinking choices with their design. The first of these was to take advantage of the hillside location by creating a basement level under the west stand, which sits on the ground level at the bottom of the hill. This reduced excavation and earth works on the west stand, while eliminating the need to have staircases on the remaining three stands, as spectators can come in half way up the stadium bowl and either go up or down the terraces. As well as allowing spectators to move in out of the stadium freely, the fabric envelope and roof was also selected to minimise M&E work.

“The porous façade allows air movement through the envelope to ventilate the bowl and keep everyone at a comfortable temperate,” Mr Armstrong explains. “They get a lot of rainfall in Cameroon – the same amount of rain in a month as we get in a year. In terms of the stands and concourses it [the fabric roof and façade] shields people from the rain, but it’s porous in terms of air flow so it keeps it cool.”

As a result, air-conditioned spaces have been limited to the players accommodation area, and the VIP and premium spaces. Catering has also been rethought to accommodate local tastes. “The world of stadium design is going high-tech with massive corporate offerings, more and more aimed at the 1 per cent because that’s where the money’s hidden,” Mr Ayres says. “In Cameroon, when you go to eat, it’s almost all street food. There are hardly any restaurants.” With this in mind, 20 street food pods have been dotted around the stadium, which local catering companies can serve from as they would along the busy streets of Douala.

The self-stabilising design of the trusses meant that only the first truss needed to be propped up. Once the second truss was erected and the two were connected, it was a stable structure. This approach was selected for multiple reasons, Mr Ayres says. First, it hugely minimised the amount of temporary work required to prop up the roof, saving on time and costs. And second, if the project had ended up running behind schedule, the team had the option of erecting the roof and façade solely on the west stand, then coming back to complete the rest once the football tournament had finished.

As it happens, all 48 trusses have been erected and the stadium is due to complete on time. The top chords of every truss come together in a diamond shape and have a glazed roof. A PVC façade supplied by Turkish subcontractor Tensaform links all the trusses, creating a fabric envelope and roof that protects spectators from the rain, while allowing air to flow freely. “The idea is that instead of being a fortress-like stadium, it’s very porous, which suits the climate. There’s no hard barrier around the stadium,” Mr Ayres explains. This means spectators can move freely in and out of the stadium’s terraces and food stalls outside, while a wider security perimeter handles gatekeeping. The result of this impressively fast-tracked and innovatively thought-out stadium project will no doubt be a jewel in Douala’s crown. Cameroon’s loss of the 2019 AFCON tournament no doubt brings an air of anti-climax to the project and to the local population, but it shouldn’t take away from a notable engineering feat.

Not just a football stadium

As well as the 50,000-seat football stadium, the scheme also includes external facilities that will be made available to the public. These include:

Source: Construction News