26, September 2020

CPDM Crime Syndicate: Journalists Say They Are Regularly Abused, Brutalized 0

Cameroon’s journalism association has called on authorities to immediately and unconditionally release journalists detained while covering anti-government protests this week.

Police detained at least eight journalists covering Tuesday’s protests, searched the homes of four of them, and seized or destroyed their equipment. At least one journalist was still in custody Thursday.

Tah Javis Mai, a freelance journalist, returned Thursday to his office in the English-speaking southwestern Cameroon town of Buea. Mai said he was arrested by police in the French-speaking coastal city of Douala on Tuesday while reporting on protests against President Paul Biya.

“The men in uniform asked that why am I using my phone to film them,” Mai said in a telephone call from Buea. “I said I am on a Skype call. They took us to that brigade in Bonaberi. One drinking alcohol poured the whiskey on me. He asked me to drink, and I refused. He poured it on my head. We were in an airtight cell. A cell for about two people, we were 15 in number with no food. Our phones were confiscated. They took everything from us.”

Mai said he was forced to sit on the ground for seven hours. He said he was released at 6 p.m. Wednesday after pressure from journalism associations and several international rights groups.

Jude Viban, president of the Cameroon Association of English-Speaking Journalists, said Mai was arrested with seven other reporters in Yaounde and Douala.

Those arrested included My Media Prime TV cameraman Tebong Christian, cameraman Rodrigue Ngassi of Equinox TV, Lindovi Ndjio of La Nouvelle Expression, and Polycarpe Essomba, Cameroon correspondent of RFI.

“We have strongly condemned the arrest of our colleagues who went out to report and not to support the protest, and they were picked up arbitrarily and detained in facilities without communication, without access to their lawyers, without access to their colleagues,” Viban said. “This is terrible for our democracy and, unfortunately, it keeps happening. It is a very difficult period to be a journalist in Cameroon.”

On Thursday, the National Syndicate of Cameroon Journalists reported that the homes of four journalists were searched by police. The report said phones, recorders and computers were seized.

Rights activist Andelbert Mvomo said Cameroon is becoming notorious for its abuses on journalists, including beatings and rights violations.

Such acts, he said, soil Cameroon’s image and disgrace its people.

Cameroonian police and the minister of territorial administration did not react to the accusations when contacted by VOA.

The Committee to Protect Journalists said Thursday that police were still holding one of the arrested journalists, Lindovi Ndjio.

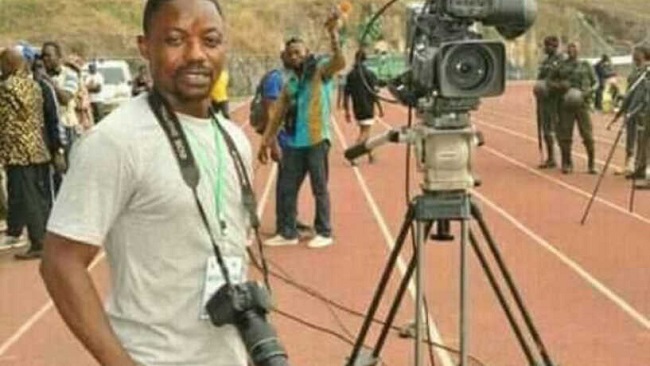

Samuel Wazizi

CPJ said it has not forgotten what happened to journalist Samuel Wazizi, who died in police custody in August 2019 but whose body has yet to be seen.

The military said it was keeping Wazizi’s body for investigations.

Source: VOA

26, September 2020

CPDM Crime Syndicate: Government Secrecy in the Management of Funds Destined for Covid-19 Response 0

As Cameroonians began to fall sick from the novel coronavirus, President Paul Biya made a plea for public solidarity to help the government support a healthcare system already collapsing under the weight of multiple security crises affecting the country.

Dozens of people and companies immediately poured money into a fund hastily created by the president. This fund should have augmented the millions of dollars in a separate Health Solidarity Fund, an emergency reserve established by the government in 1993, into which healthcare facilities pay 10 percent of their revenues each month. These revenues largely come from patient fees, raising the cost of health care, already unaffordable for many.

However, the government has managed both these funds in secrecy, obstructing the public’s ability to track public resources.

It is not clear if and how the government has spent these funds, nor the $226 million from the International Monetary Fund it received to support its Covid-19 response, among other international assistance. As the virus swept across the country, medical staff and others told us in June that their hospitals had received no extra financial assistance, hampering their ability to treat patients or provide healthcare workers with adequate protective equipment.

Only after enormous public pressure, citing the “urgency of transparency,” did the government publish, on July 29, some basic information in a two-page statement about how it spent about 22 billion FCA ($40 million), which it said was its total expenditure to respond to Covid-19 in the preceding five months.

Funding from the ADB and the IMF

The information provided is too general to allow for meaningful public oversight – saying only that, for example, 1.75 billion FCA ($3 million) went toward “rehabilitating, renovating, and extending” isolation areas in three hospitals in Yaoundé, the capital. The statement similarly provides a generic list of equipment to account for another 3.92 billion CFA (nearly $8 million) attributed to “procurement of medical equipment distributed to facilities.”

And what little is included may not be entirely accurate. Observers who visited the three Yaoundé hospitals and spoke to staff there two weeks after the Health Ministry published the statement were unable to identify any new construction work to prepare for Covid-19 patients, although two had set up tents outside as testing sites. A sign at the General Hospital of Yaoundé dated July 16 announced that the hospital would no longer accept Covid-19 patients.

Watchdog groups such as the Association for the integrated development and Interactive solidarity (ADISI), with its digital platform Data Cameroon, have also pointed out that the $40 million does not account for all the funds the government received to support its Covid-19 response. The Health Ministry statement included a list of about 65 individuals and companies who donated around 1 billion FCA ($1.8 million) to the president’s solidarity fund. But it hasn’t made public any information specific to the fund’s revenues and disbursements, which appear not to be governed by any legislation. And the total sum the Ministry says it spent is far smaller than the amount it received in international assistance for more than 43 Covid-19 projects, including $100 million from the African Development Bank.

The International Aid Transparency Initiative tracks funds for these projects, but does not include comprehensive details on expenditures. Nor does the tracker account for the $226 million in emergency assistance the government received from the IMF in June.

More than 20,000 cases and 416 deaths

In a letter requesting the loan, the finance minister cited the importance of the funds “to cover urgent needs to upgrade the health system.” The letter committed to publishing all procurement documents related to Covid-19 expenditures, including the names of the real owners of companies awarded contracts, but we were unable to find any such contracts.

In his letter, the minister also promised to publish the results of an independent audit by the end of 2020 fiscal year, which passed on June 30 without any news that an audit is even in progress.

Tracking this money is about more than the government reciprocating public solidarity with accountable governance; it is key to ensuring funds crucial for fighting a pandemic are fully and fairly distributed across the country. Cameroon reported more cases and deaths than most countries in Central Africa – nearly 20,000 cases and 415 deaths as of September 10, according to the World Health Organization. Yet many hospitals remain woefully unprepared six months into the pandemic.

We spoke to a doctor who works in a hospital in the North-West region, which has been hard- hit by violence since late 2016 and whose medical facilities have been repeatedly attacked by both government forces and armed separatists. He said that the 10 health facilities in his district received a combined 10 million FCA (around $17,000) in early August. Prior to that, his hospital, had only received 12 masks, 20 boxes of gloves, and four full body gowns for almost 50 employees, he said.

The money enabled his hospital to buy personal protective equipment for some staff, medicine, and two oxygen machines, he said, but it didn’t come close to meeting the needs of the hospital needs, which still lacks sufficient protective equipment for most staff, as well as adequate access to electricity and an ambulance. And the money arrived tragically late: a nurse at a nearby hospital died from Covid-19 in June.

Cameroonians have demonstrated their solidarity. It’s well past time for the government to do the same and publish a full accounting of the Covid-19-related spending, including from the Health Solidarity Fund.

Culled from Human Rights Watch