2, April 2021

US Department of State releases 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices in Cameroon 0

Cameroon is a republic dominated by a strong presidency. The president retains power over the legislative and judicial branches of government. The ruling political party, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement, has remained in power since its creation in 1985. The country held legislative elections on February 9, which were marked by irregularities. The ruling party won 152 of 180 National Assembly seats. Paul Biya has served as president since 1982. He was last reelected in 2018 in an election marked with irregularities.

The national police and the national gendarmerie are responsible for internal security. The former reports to the General Delegation of National Security and the latter to the Secretariat of State for Defense in charge of the Gendarmerie. The army is primarily responsible for external security and shares some domestic security responsibilities; it reports to the minister delegate at the presidency in charge of defense. The Rapid Intervention Battalion reports directly to the president. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain control over security forces. Members of security forces committed numerous abuses.

In July jailed separatist leader Julius Sisiku Ayuk Tabe announced he talked with the government regarding the prospects for peace in the Anglophone regions. The government, however, denied Ayuk Tabe’s announcement, and other separatists opposed the talks. Cameroon Renaissance Movement president Maurice Kamto urged Cameroonians to stage nationwide peaceful protests on September 22 to demand a resolution to the crisis in the Anglophone regions and for electoral reform before the December 6 regional elections. Hundreds of protesters were arrested, including journalists, and Kamto was placed under unofficial house arrest.

Significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings by security forces, armed Anglophone separatists, Boko Haram, and ISIS-West Africa; forced disappearances by security forces; torture and cases of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by the government, Cameroonian peacekeepers deployed to UN missions, and nonstate armed groups; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrests; political prisoners or detainees; politically motivated reprisal against individuals located outside the country; serious problems with the independence of the judiciary; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; serious restrictions on freedom of expression, the press, and the internet, including violence, threats of violence, or unjustified arrests or prosecutions against journalists, censorship, and criminal libel laws; substantial interference with the right of peaceful assembly and freedom of association; serious restrictions on freedom of movement; inability of citizens to change their government peacefully through free and fair elections; restrictions on political participation; serious acts of corruption; lack of investigations and accountability for violence against women; unlawful recruitment or use of child soldiers; trafficking in persons; crimes involving violence or threats of violence targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or intersex persons; and the existence or use of laws criminalizing same-sex sexual conduct between adults.

Although the government took steps to identify, investigate, prosecute, and punish officials who committed human rights abuses, it did not do so systematically and rarely made the proceedings public. Some offenders continued to act with impunity.

Culled from U.S. Department of State

2, April 2021

Violence in Southern Cameroons takes high civilian toll 0

Worsening violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions is taking an increasingly heavy toll on civilians, with renewed attacks against schools and a spate of incidents involving improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and extrajudicial killings documented in recent months.

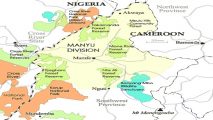

These attacks are the latest escalation in the nearly five-year conflict between government security forces and armed separatists which has displaced more than 700,000 civilians and forced another 63,800 across the border to Nigeria, according to a United Nations report this week.

Overall, the UN estimates three million of the four million people in Cameroon’s Northwest and Southwest have been impacted.

The Anglophone conflict began in late 2016 when government security forces used lethal force to put down peaceful marches by lawyers and teachers protesting against perceived marginalisation by the country’s majority Francophone government.

In response, more than 30 armed separatist groups formed to fight for an independent nation they called Ambazonia. A self-declared Interim Government of Ambazonia also emerged and is run largely by Anglophone Cameroonians living in Europe and the United States.

Separatists are known locally as “the boys” and consider themselves “restorationists” or “freedom fighters”. Representatives from the Cameroonian government refer to them as “terrorists” in public statements.

At least 4,000 civilians have so far been killed in the Anglophone regions, a toll that surpasses that of the country’s Far North region where Boko Haram has been waging an armed campaign since 2014.

Shifting conflict dynamics

In the first years of the conflict, there was a clear “cycle of violence”, according to Chris Fomunyoh, a senior associate and regional director for Central and West Africa at the National Democratic Institute.

“Every time the armed groups attacked the military and someone in uniform was killed, then the military goes into that vicinity or that neighbourhood ‘in pursuit of the boys’ and mows down civilians”.

However, during the past year, the number of clashes between separatist groups and security forces has declined while there has been an uptick in attacks against civilians, according to data collated by the United Nations and the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) Project.

“The [conflict] dynamics keep changing every day,” said Esther Njomo, a human rights advocate based in the Southwest region. Separatist groups, in particular, have intensified targeted attacks against civilians and aid workers, Njomo said.

Since January 2021, separatists have been accused of abducting a local physician, burning down public infrastructure, such as markets and post offices, and killing at least five civilians, according to media reports and NGOs. On February 13, suspected separatists killed three traditional village leaders and kidnapped 30 civilians.

In the same timeframe, separatists have also carried out at least 27 attacks involving IEDs in 13 towns across the two regions, more than all previous years of the conflict combined, according to UN reports and ACLED data.

Attacks with IEDs usually target military personnel, convoys, and buildings. Twelve documented attacks occurred in Bamenda, the capital of the northwest region. At least 10 government security personnel have been killed and four civilians wounded in these attacks.

Fombat Forbah Dieudonne, a spokesperson for the Ambazonia Restoration Forces, a separatist group linked to the interim government, denied that any groups involved in the separatist movement have carried out abductions or killed civilians.

“As concerns the IED[s], I have no knowledge of our people being capable of manufacturing such. However, we shall defend using any means possible, according to international law, ourselves for as long as this colonialism and genocide continues,” Dieudonne said.

Government security forces have also faced accusations of raiding villages, burning homes and arbitrarily arresting and killing dozens of civilians, according to local and international NGOs.

In January, military forces raided Mautu village in the southwest region and killed nine civilians, including a woman and a child, Human Rights Watch said. A month later, a video of government security forces brutally beating the brother of a suspected separatist in a town called Ndu circulated on social media.

Widespread condemnation of the video led to the Cameroonian government arresting eight officers involved.

A spokesperson for the Cameroonian military declined to comment on the continuing crisis.

Renewed attacks against schools

In October 2020, the lifting of school closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic sparked renewed attacks targeting learning institutions.

Between October and December 2020, the UN recorded 35 attacks on schools including the “killing, torture and abduction of students and teachers, as well as arson of education facilities”, according to an internal report provided to Al Jazeera.

Of those attacks, 30 were carried out by separatist groups resulting in 10 civilian deaths and 67 abductions.

The five other incidents involved government security forces including the “accidental discharge of weapons” near schools and resulted in five civilian injuries.

Schools have been a main point of attack since the beginning of the conflict when separatists called for a boycott on education to draw attention to the increased use of French in the classroom and reliance on monolingual French-speaking teachers.

Human Rights Watch previously documented that separatists set fire to schools and attacked students and staff who did not comply with the ban.

Dieudonne denied that separatists ever banned school attendance. “We have continually said that the security situation does not provide the enabling environment for schooling.”

He also denied that any groups tied to the separatist movement have ever attacked schools.

Towards a ‘fragile state’

Once considered a beacon of stability in Central Africa, Cameroon is now facing three protracted humanitarian crises.

In addition to the Anglophone conflict, Cameroon is struggling to respond to an influx of more than 200,000 refugees to its East, Adamawa, and Northern regions from neighbouring Central African Republic.

In the Far North region, there has been a spike in attacks carried out by Boko Haram. The United States, a main defence partner to Cameroon, has reduced its funding for military assistance due to continuing human rights violations in the country for the past two years.

The International Crisis Group has also documented “rising ethno-political tensions” after controversial 2018 presidential elections pitted ethnic Bulus, to which long-running President Paul Biya belongs, and the closely related Beti people against the Bamileke people, to which Biya’s main opposer, Maurice Kamto, belongs.

“The state of fragility of Cameroon as a state has grown exponentially for five years,” Fomunyoh said. “I don’t see an easy outlet in the short-to-medium term unless a political settlement is arrived at soon.” SOURCE: AL JAZEERA