Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

15, January 2025

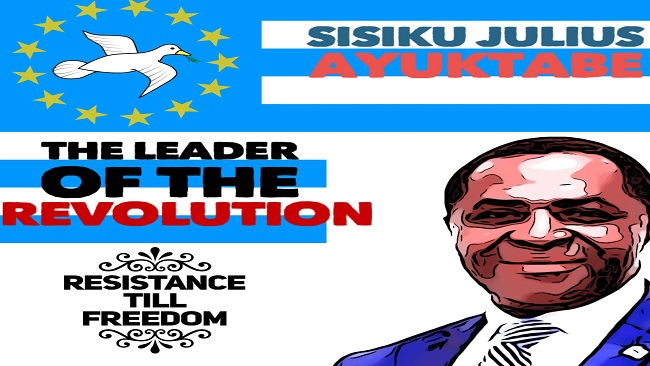

Sisiku Ayuk Tabe leading the Ambazonia revolution from behind bars 0

by soter • Cameroon, Editorial, Headline News, News

Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe has already served seven years of his life sentence at the Yaoundé principal prison in Cameroon, but he is not ready to budge an inch in the political beliefs that landed him there. “The fight for homeland is existential and non-negotiable – being part of the struggle is a calling and not a vocation,” he tells the Guardian.

The 59-year-old computer engineer and former president of a breakaway state is still fighting his revolution from jail. As Cameroon’s civil conflict festers, his quest remains the freeing of his anglophone community from what he sees as the shackles of a francophone Cameroonian state.

“We have an obligation – dead or alive – to bequeath to our children a nation that they can call theirs, something we have been deprived of for too long,” he says.

On 1 October 2017, Ayuk Tabe declared the independence of “Ambazonia” – Cameroon’s English-speaking north-west and south-west regions, known during the colonial era as the British Southern Cameroons – after a government crackdown on protesters.

In November 2016, lawyers from the regions had marched against the government’s decision to appoint francophone magistrates in anglophone courts, seeing it as a threat to common law. Educators followed with their own protests after French-speaking teachers were imposed on anglophone schools.

Ayuk Tabe’s de facto presidency ended in January 2018 when he was arrested in the Nigerian capital, Abuja, allegedly by Nigerian special forces.

He was extradited with nine others to Cameroon, despite claims that many of them were refugees and asylum seekers. The move was later ruled illegal by the UN.

In August 2019, a military court in Cameroon sentenced Ayuk Tabe and his aides to life imprisonment on terrorism and secession charges. They were fined FCFA 273bn (about $428m).

The UN human rights council and three federal high court of Abuja judgments have ordered their release but none of these rulings have been respected, and the men remain in prison.

Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe

“How can civilians be charged and sentenced in military courts?” Ayuk Tabe asks. “Before any court in Cameroon, all Southern Cameroonians have a life sentence reserved for them just because of who they are. We are taking one for our nation and we pray it should be the last for all Southern Cameroonians.”

The declaration of Ambazonia’s independence triggered deadly clashes between anglophone armed separatists and the state security forces, which resulted in widespread atrocities against the civilian population.

More than 6,000 people have since been killed, according to the International Crisis Group, although Ambazonia’s leadership claims the figure is far higher. More than a million people have been displaced within and outside the country. Thousands of people suspected of supporting the revolt have been detained and many are still awaiting trial.

When the Guardian arrives at Yaoundé prison it is teeming with visitors – mainly relatives, friends and acquaintances – who have come to see Ayuk Tabe and those detained with him.

With his customary charm, Ayuk Tabe speaks to everyone, telling them he has three key messages to send to his people back home: “Tell them that we will go to Buea whether [president] Mr Paul Biya likes it or not; come rain or shine. Tell them that we will hoist the Ambazonian flag in Buea and that once this is done, we will sing the Ambazonian anthem – until that happens, the struggle won’t end.

“Finally, tell them to take good care of the needy of the struggle – families who have lost loved ones, the internally displaced, refugees, those in detention, not forgetting the heroes of the struggle – the men and women who have opted to fight and die for the struggle,” he says.

After singing a few verses of the national anthem, Ayuk Tabe gets up to move around and hug a few of his visitors.

“We call them our guardian angels because they baby us,” he says, adding that these supporters have helped the Ambazonian inmates at the prison by bringing them food and bedding.

He says conditions at the prison are difficult: they’re given flimsy beds without mattresses and a single “terrible” meal a day.

“But Ambazonian detainees in this prison feed themselves twice a day, thanks to the generosity of our relatives and friends – they don’t consume anything offered by this prison except the water used for bathing,” he says.

Cameroon was first colonised by Germany between 1884 and 1916, then divided between France and Britain after the first world war. French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, joined by English-speaking Cameroonians through a federation a year later.

The French-speaking area makes up about 80% of the country and the English-speaking part about 20%, both in territory and population. A referendum in 1972 repealed the country’s federal structure which had guaranteed rights and secured a distinct educational, judicial and political system for the minority anglophone section.

Close to the principal prison is the Yaoundé central prison, where nearly 300 anglophone detainees are being held. Abdul Karim Ali, 43, a Muslim scholar, IT engineer and business consultant, has been awaiting trial here since February 2023.

Ali was arrested in the north-west regional capital, Bamenda, on 11 August 2022, for criticising the injustices committed against his anglophone community. He was detained for three months in a windowless room with no toilet and denied access to his family and lawyers for three weeks, he says. Transferred to the dreaded State Defense Secretariat detention facility, he spent another three months there before being transferred to Yaoundé central prison.

Abdul Karim Ali

“I was abducted to be silenced. Not just because I believe in the right to self-determination of the people of Southern Cameroons, but because I defended those rights and called out the occupying regime of Yaoundé,” Ali says.

“Like other activists, I have been accused of terrorism and secession. I consider the military court incompetent to try a civilian like myself. I have made it known that I’m not going to court. I want to be tried in a civilian court and in my Bamenda home town where I was abducted.”

Ali says he has no issue with the Cameroon government, but that it has a problem with Southern Cameroons.

“I’m in their captivity just like every other freedom fighter. I don’t wish anybody to experience the prison conditions I have endured.”

He says the situation in Cameroon’s north-west and south-west regions is one of “torture, genocide, colonisation, incarceration and dehumanisation” – the consequence of the annexation that started in 1961.

He blames the current conflict on the “incomplete decolonisation” of Southern Cameroons by Britain and Cameroon’s annexation of the territory thereafter.

“The Cameroon government declared war on Southern Cameroons. They are the invading bully and illegitimate state actor. So, the burden to call for a ceasefire lies on them,” he says.

Peace, he says, would require the unconditional release of all Southern Cameroonians; the demilitarisation of the territory of Southern Cameroons; and dialogue between the two parties.

Ali eats once and prays five times a day. Otherwise, his daily schedule includes exercising in the prison courtyard and reading.

“History provides us with enough verdicts: every dictatorship collapses and every annexation comes to an end,” says Ali, whose political activism was inspired by Gandhi. “Today or tomorrow, the people of Southern Cameroons will be given the right to determine their political future,” he says.

Sitting nearby in the prison hall is another detainee, Mancho Bibixy Tse, a 40-year-old journalist and activist.

In November 2016, Mancho mounted a coffin at a crowded roundabout in Bamenda to denounce the social and economic injustice of his anglophone community, which became known as the “coffin revolution”.

He was arrested, charged with terrorism, secession, rebellion, inciting civil war, and spreading false information through social media, and sentenced to 15 years.

In July 2019, Mancho led a protest against conditions at the prison, which earned him an additional 18 months.

Mancho says frustrations about 60 years of Cameroon’s occupation of Southern Cameroons led to his activism. The idea of using a coffin came about “spontaneously”.

“I have always wanted positive change wherever I found myself – I have been a freedom fighter all my life,” he says, maintaining that he has never regretted – and will never regret his actions.

“I am the first person who declared the Ambazonian revolution,” he says. “And I will do it over and over again if the opportunity shows up. I am ready to die for freedom.”

Back at the Yaoundé principal prison, Ayuk Tabe is hopeful of ultimate victory.

“Rather than waning, our independence ideology is gaining more ground. Proof is that we are in the eighth year of the struggle and a Cameroon military victory is still very far-fetched,” he says.

“No matter how long this darkness has been, victory is assured and on the way. We all, eight million Ambazonians, share a common pain and plight. We cannot continue this life of servitude and pass it on as a legacy to our future generations.”

Culled from The Guardian