Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

23, April 2019

A raft of crises now face Cameroon 0

Soccer fans in Cameroon were undoubtedly dismayed in January when the Confederation of African Football stripped the country of its hosting the 2019 June-July African Cup finals. The body cited security issues and lack of preparation in transferring the honor to six-time African Cup host Egypt.

But the recent ouster of two long-serving African presidents—Abdelaziz Bouteflika in Algeria and Omar al-Bashir in Sudan—has intensified the focus by Cameroonians on the nearly 37-year reign of their aloof 86-year-old president, Paul Biya. Citing corruption and political marginalization, opposition figures and Anglophone region activists strive to make Biya the third African leader ousted in 2019 as a result of popular protests. So far, Cameroon’s security services have managed to suppress protests that have broken out, but the Cameroonian diaspora in Europe has been effective in generating sustained attention for change.

While only intermittently covered by American media, and with the United Nations and African Union mostly mute, Cameroon is currently engulfed in three separate crises.

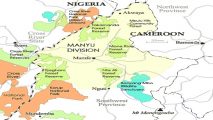

First, since 2014, Boko Haram has terrorized Cameroon’s far north region, adjacent to Nigeria’s Borno State (where Boko Haram was founded in the city of Maiduguri) with murders, kidnappings, and destruction of infrastructure. Despite military support, training, and equipment from the United States and others, Boko Haram in Cameroon remains a persistent, serious threat. Tens of thousands are displaced and livelihoods destroyed. With Boko Haram incursions on the rise in 2019, Yaoundé’s brutal security responses are so tainted with credible human rights allegations that the United States in February announced a reduction in its assistance.

Second, peaceful protests against linguistic and political marginalization in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions erupted in 2016. Anglophones account for approximately 20 percent of Cameroon’s population, with the rest considered Francophone (in addition to about 200 local languages). These protests quickly escalated in 2017 into a violent secessionist insurgency and counter-insurgency. Anglophone separatists hoping to create an independent state of “Ambazonia” in the northwest and southwest regions of Cameroon have attacked soldiers and government installations and killed civilians perceived to be government sympathizers. Local and international human rights activists have documented scorched-earth military reprisals and extrajudicial killings. With positions hardening on both sides, the government rebuffed mediation and dialogue facilitation offers by the United Nations and others, demanding that the United Nations Secretary General’s Special Representative for Central Africa Francois Fall, a former foreign minister of Guinea, end his quiet diplomacy in the Anglophone region. During his March 2019 trip to Cameroon in which he encouraged peaceful resolution of the Anglophone crisis, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Tibor Nagy was sharply criticized by pro-government sources for “interference.”

In addition to the heavy burdens imposed by the Boko Haram and Anglophone crises, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that Cameroon—with a population of 24 million—hosts nearly 400,000 refugees fleeing violence in neighboring Nigeria and the Central African Republic.

Now, with the Algerian and Sudanese protests leading to the respective militaries’ removal of two long-serving presidents, previously disparate and quiescent opposition against President Paul Biya has mobilized to create Cameroon’s third, and—while not yet violent—potentially most serious crisis. With previous constitutional term limits abolished in 2008, Biya, who has ruled since November 1982 (and who served as prime minister from 1975 until 1982), was sworn in November 2018 for his seventh presidential term. The official election results, disputed by the opposition, gave him 71 percent of the vote, with opposition leader Maurice Kamto in second position, with just over 14 percent.

For years, fatigue and disenchantment with Biya’s rule has simmered below the surface in Cameroon and boiled openly in the Cameroonian diaspora. Complaints and jokes focus on his frequent and lengthy sojourns in Europe, corruption, aloofness, curtailment of civil liberties, lifestyle of his younger wife Chantal, and (given Biya’s age of 86) lack of any transparent succession planning. The lopsided official election results provoked protests in Cameroon and in diaspora communities, with Kamto claiming victory. The January 2019 arrest of Kamto and scores of protestors in the port city of Douala attracted scant notice in the media outside of Cameroon (despite condemnations from Nagy, EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy Federica Mogherini, and others) but reinforced the opposition protests, especially in Europe. Expats attacked Cameroon’s embassies in Paris and Berlin and threatened to storm Geneva’s Intercontinental Hotel, should Biya, a frequent resident, again check in.

Now, with the removals of Bouteflika and Bashir, anti-Biya protesters hope to attract attention with new chants: “It can happen in Sudan; it can happen in Cameroon.” So far, Cameroon’s security services have managed to prevent sustained, mass demonstrations at home. As was the case in Algeria and Sudan while the protest movements swelled, it is not clear how the military would react should the Cameroon opposition movement gain momentum. The military’s performance in the Anglophone and Boko Haram violence is not encouraging, in terms of adherence to human rights norms. But fighting Boko Haram terrorists and Anglophone secessionists simultaneously may give Cameroon’s military leaders pause before taking on, in addition, political protestors in Cameroon’s Francophone political heartland, should Sudan-style mass protests materialize. Biya himself is taking no chances: Unusually for him, he has remained in Cameroon for more than 200 days without travel to Europe.

What is clear is that this is the time for conflict prevention efforts by African or other leaders, in hopes of moderating any response to protests in order to stave off the potential for a third Cameroon crisis turning violent. The problem is identifying a person, institution, or country with influence on Biya, who has been as aloof from his peers as from Cameroon’s citizenry. Despite his frequent and extended absences from Cameroon, he has not used the time abroad to bond with other leaders, rarely attending the annual United Nations General Assembly and only participating in a single African Summit in the last seven years. (Biya attended the March 2013 African Summit in Malabo, probably due to his shared Fang ethnic connection to Equatorial Guinean President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo.) Compared to other heads of state in Francophone Africa, Biya is not especially close to Paris. Given Biya’s de facto part-time residency in Switzerland, and in light of the Cameroonian diaspora’s focus on Geneva, the Swiss may have both interests and leverage, especially if backed by others such as Nagy’s, Mogherini’s, and African Union interventions.

Yet as failed conflict prevention efforts globally demonstrate, persuading any national leader to accept outside help to address a domestic political issue is hard. Biya’s response to U.N., U.S., and other efforts to focus on peaceful resolution of the Anglophone conflict is not encouraging. Regional and international unity to demand a political approach to address Anglophone grievances and expand political space (including release of opposition activists, including Kamto) might force Biya to adjust his approach but will require leadership by the United States or another power to muster. Credit agencies have already noticed that all is not well in Yaounde, with Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s both recently indicating a “negative outlook” to their respective B and B2 credit ratings.

Cameroon’s immediate neighbors are themselves facing challenges and are not in positions to offer much in the way of help or example. To Cameroon’s northwest, parts of Nigeria remain terrorized by Boko Haram. To Cameroon’s east, the Central African Republic remains deeply unstable and violent, despite the February agreement signed in Khartoum by 14 militias. South of Cameroon, Gabonese President Ali Bongo Ondimba claimed victory in a disputed 2016 election (extending his family’s nearly half-century control over Gabon) but has since October 2018 been absent from Libreville for long stretches of time for health issues. On Cameroon’s southeastern border, the Republic of Congo under President Denis Sasso-Nguesso (no stranger to controversial lopsided election results) has used violence against demonstrators in the Pool region, leading to tens of thousands of displaced, in addition to hosting thousands of refugees fleeing violence in the neighborhood Democratic Republic of Congo. This part of Africa has no shortage of crises, but little in the way of obvious solutions.

Culled from The Brookings Institution