Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

27, December 2017

Anglophone crisis sliding into a rebellion 0

A secessionist push in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions is on the brink of a full-blown revolt, threatening political stability in a country ruled by one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders. Following a crackdown on independence supporters who tried to raise flags on government buildings in the central African nation’s English-speaking regions in October, at least 16 members of the security forces have been killed in attacks the government blames on the activists. This month a mob of 200 men besieged a paramilitary police station, according to the government.

Vital Ports

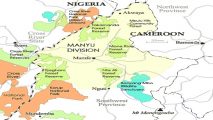

Cameroon’s English-speaking minority, about a fifth of the population, has complained of marginalization for decades and many highly educated Anglophones have moved abroad. The country, whose roads and ports are vital for landlocked neighbors such as oil-producing Chad, was split after World War I into a French-run zone and a smaller, British-controlled area.

Radical factions of the protest movement in the Northwest and Southwest regions now refer to the area as Ambazonia and discuss armed struggle on social media. About 20 percent of the population in the affected regions is estimated to support secession, according to the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

The unrest comes as Cameroon’s army struggles to halt a spate of bombings and raids by the Islamist militant organization Boko Haram near the northern border with Nigeria. While Boko Haram forced thousands of Cameroonians to flee their homes last year, the secession campaign poses a much bigger threat to the government, Heungoup said by phone from Nairobi, Kenya’s capital.

“Even if Boko Haram killed a lot of people, it was clear from the onset that they would never threaten or capture the state,” he said. “But the Anglophone crisis calls the foundations of the Cameroonian state into question.”

Heavy-handed Response

President Paul Biya, who calls the secessionists criminals, is seeking to extend his 35-year rule in elections next year. Biya is the continent’s second-longest serving head of state, after Teodoro Obiang of neighboring Equatorial Guinea. Robert Mugabe, who ruled Zimbabwe since 1980, resigned in November.

Ambazonia now has a self-proclaimed president, a flag and an official government website. Commonwealth Secretary-General Patricia Scotland spent five days in Cameroon this month in an attempt to defuse the crisis.

“When this crisis was in its beginning stages, the government thought it could kill a few protesters, arrest others and heavily militarize the North West and South regions for the crisis to be over,” said Shadrack Mbiwang, an activist who claims to be a member of the Ambazonia army. “This time around, we are ready to fight and fight till the restoration of our statehood.”

Culled from Bloomberg.com