Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

28, February 2017

Anglophone Crisis: There’s more to Cameroon’s protest than meets the eye 0

For three activists from western Cameroon who joined a call for the recognition of their linguistic preferences, last week didn’t bring any good news. The lawyer, teacher and journalist have been locked up since mid-January, and their case before a military tribunal was again suspended on 13 February, to 23 March. Cameroonian jails are notorious for not being easy on their inmates.

The arrests of Agbor Balla, Fontem Neba and Mancho Bibissi came amid a crackdown against Cameroonians from the Anglophone regions who participated in anti-government protests these past few weeks. The three, who are among at least 100 people arrested, are charged with sabotage, terrorism and inciting secessionism and civil war – charges that could carry the death penalty.

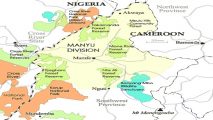

Meanwhile, the Internet in northwest and southwest Cameroon, the two affected Anglophone regions of the country (out of a total of 10), has been cut off completely for over a month. This decision is estimated to be costing the country US$1.39 million. The organisation Access Now has appealed to the Internet service providers to ignore a directive by the government in Yaoundé and to re-establish the connections.

The Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium, a well-known rights group, has also been banned since civil society groups and students took to the streets in mid-November last year; and local independent media have been shut down. The protest action was marked by violent clashes between stone-throwing youths and the police, as well as stay-aways and boycotts.

The main gripe of these groups is that the bilingual principle enshrined in the constitution is not respected. Instead, English-speakers feel they are forced to assimilate and accept what the predominantly Francophone majority dictates.

The crisis has historical roots. Cameroon went from being a German colony, to two separate colonial territories ruled by France and Britain after World War I up until independence in 1960. Following a plebiscite in 1961, the British part was reunited with the French Cameroon. The Francophone authorities that have ruled the country since then have pursued a centralised system of government after a brief period of federalism that officially ended in 1972, following a referendum.

Teachers and students say that the central government should send Anglophone rather than French-speaking teachers to schools in the two regions where English dominates. Lawyers also complain that the British Common Law, used in British Cameroon during colonial times, should be maintained in the region. The use of French in the administration limits access and discriminates against those who speak English, they argue.

Some analysts also emphasise that the revolt in the northwest is symptomatic of a larger problem of governance and a state characterised by corruption and inertia. Between 2000 and 2009, northerners – predominantly Muslims – also complained of marginalisation and the absence of the state.

In 2008, protests against soaring food prices rocked the country, as it did periodically since the 1990s. This also led to a violent crackdown by the government. ‘There have been many missed opportunities by the government to handle this issue adequately,’ says Fonteh Akum, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, who has previously written on the Anglophone zones in Cameroon.

Attempts at implementing a federal system where Anglophones would have their own courts with effective administrative decentralisation have been undermined by ‘irresponsibility and corruption,’ he says. A decentralisation framework already exists, but has been selectively implemented.

‘The government initially argued that this was a non–issue and that these are secessionists. They refused to acknowledge that Anglophones have legitimate claims,’ Cameroonian scholar Achille Mbembe points out that the claims by Anglophones started as linguistic and cultural, but have become far more political. ‘They don’t feel there is a place for them in this centralised state,’ Mbembe, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, told ISS Today.

Anglophones are treated like second-class citizens who don’t benefit from the oil revenues that are situated in their region. Very few important government positions are occupied by Anglophones. ‘There has never been an Anglophone minister of defence or finance. People complain that the administration doesn’t speak their language’.

However, Mbembe says the calls for secession by civil society groups and on social media is ‘very dangerous’. These started in the mid-1990s, with the first call for secession by the Southern Cameroon National Council. ‘The cost of secession is just too great,’ says Mbembe, who believes that Africa should move towards greater pan-Africanism instead of dividing in small ‘micro-states’.

He says the regime of President Paul Biya, who has been in power for 35 years, is characterised by ‘inertia, indifference and abandonment’.

Opinions differ as to how much support there is for the Anglophone cause in the rest of Cameroon. Some say that in the initial stages of the protests, Francophone Cameroonians supported the calls by trade unions and students. These were seen as legitimate. However this sympathy has waned due to some radical views – expressed on social media – that a ‘genocide’ is being planned against western Cameroonians. The majority Francophone inhabitants also reject the secessionist claims.

Yet there have also been expressions of solidarity with the Anglophone cause countrywide. Following the African Cup of Nations victory by the Cameroonian Lions last month, goalkeeper Fabrice Ondoa, who is Francophone from Yaoundé, dedicated the African Cup to ‘our brothers from Bamenda’ [the capital of northwestern Cameroon]. ‘We need a united Cameroon,’ he said in a message widely circulated on social media. ‘I am from Bamenda, for you,’ he concluded in English.

Thus far, there has been little reaction from the international community. The African Union (AU), apart from one statement expressing concern over the situation, hasn’t been involved in any efforts to calm the situation in western Cameroon. It is likely that the AU is adopting a wait-and-see attitude, and will only act if the situation worsens.

What matters most to the international community is that Cameroon remains stable and continues to be part of the global fight against terrorism. (The government has joined forces with Nigeria, Chad and Niger to root out Boko Haram.)

For now, the instability, characterised by various waves of contestation, is up to Cameroonians to handle. Biya (84) is set to stand for re-election next year – and the expectation is that he will win another mandate, despite the growing popular displeasure with his rule.

Culled from Defenceweb