5, June 2024

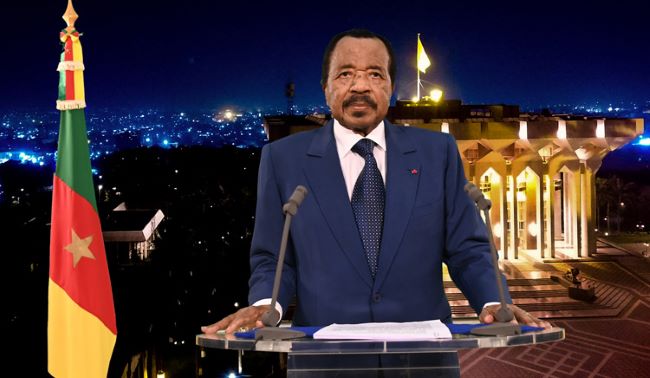

Yaoundé: Biya green lights €79.11mln agricultural expansion funding 0

President Paul Biya has ratified two financing agreements totaling €79.11 million (about CFA52 billion). The deals aim to support the implementation of the Hydro-Agricultural Development Project covering 15,280 hectares in the Mbéré, Vina, and Faro-et-Déo departments in the Adamaoua region. The first agreement, valued at €76.23 million (around CFA50 billion) is a buyer credit and the second, worth €2.89 million (nearly CFA1.89 billion), is a commercial credit. These deals were concluded with the British group Standard Chartered Bank on January 30 in Yaoundé.

This financing is part of the three-year Emergency Plan to Accelerate Economic Growth in Cameroon (Planut), specifically focusing on territorial development. It marks the initial phase of an ambitious program to develop 35,000 hectares of cultivable land in Cameroon. The project, to be technically implemented by the Spanish company Incatema, involves constructing irrigation systems for extensive cultivable areas, building 100 kilometers of roads, establishing several production units, and procuring various agricultural equipment.

Additionally, the project includes conducting a financial study to ensure youth employment and facilitate the marketing of agro-pastoral products. Besides enhancing food security, this initiative is expected to boost the country’s economic growth, as outlined by the Ministry of Economy, Planning, and Territorial Development. It also aligns with Cameroon’s commitments in combating climate change, including its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

In the medium term, the project aims to enhance the capacities and productivity of a national agriculture resilient to climate change. Long-term objectives involve developing a smart second-generation agriculture, combining structural transformation and environmental preservation. Furthermore, it aims to “give stronger impetus to the government’s import-substitution policy, aimed at producing more to meet domestic demand and reduce imports,” according to Economy Minister Alamine Ousmane Mey.

Source: Business in Cameroon

6, June 2024

419: Cameroonian nabbed for ‘black dollar’ scam in the Philippines 0

The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) has arrested a Cameroonian national for allegedly collecting at least P4 million in exchange for fake dollar bills at a hotel in Makati.

Members of the NBI Cybercrime Division posed as investors to apprehend Khan Fonkam, who allegedly promised to convert fake US dollars into real currency using a chemical process.

The NBI agents recovered the fake US dollars in Fonkam’s hotel room.

The scheme, known as the “black dollar” scam, involves convincing victims to pay money for chemicals purportedly needed to convert counterfeit currency into real dollars.

The suspect’s arrest stemmed from the complaint of a victim, who reported that Fonkam gave him a suitcase of fake money in exchange for P4 million.

The NBI said the victim met Fonkam through social media.

“The agreement was to split the amount, with each of them getting $2.5 million. The victim shelled out P4 million to buy the chemical,” Van Homer Angluben, executive officer of the NBI Cybercrime Division, said.

Fonkam is being held on charges of estafa and illegal use of false treasury bank notes.

Source: The Philippine Star