3, May 2019

Southern Cameroons and Cameroun: Events of 2018 0

Cameroon, a country previously known for its stability, faced violence and serious human rights abuses in 2018. The country endured abusive military operations against a secessionist insurgency in two Anglophone regions, attacks by the Islamic militant group, Boko Haram, in the Far North, and a worsening humanitarian crisis. President Paul Biya, 85, won a seventh seven-year term on October 7.

In the South West and North West, government security forces have committed extrajudicial executions, burned property, carried out arbitrary arrests, and tortured detainees. A Human Rights Watch report documented a range of abuses by both sides in the Anglophone regions, including arson attacks on homes and schools. According to the International Crisis Group, government forces and armed separatists killed over 420 civilians in the regions since the crisis escalated in 2017.

The humanitarian consequences of the Boko Haram attacks and separatist insurgency are of growing concern. As of November, the United Nations estimated that more than 244,000 civilians were displaced in the Far North and 437,500 in the Anglophone North West and South West regions. About 32,600 Cameroonians found refuge in Nigeria. Also, Cameroon has continued to forcibly return Nigerian asylum seekers, fleeing Boko Haram attacks in northeastern Nigeria.

While the government maintained it did not tolerate serious crimes committed by security forces, it failed to demonstrate progress in investigating and punishing them.

On October 22, Cameroon’s Constitutional Council validated Paul Biya’s reelection, with 71.28 percent of the votes. The council’s decision was immediately contested by one of Biya’s rivals, Maurice Kamto, who claimed the results had been altered. In early November, dozens of pro-Kamto protesters were arrested in Bafoussam, Western region. Biya was sworn-in for a seventh term as president on November 6.

The Anglophone Crisis: Abuses on Both Sides

In the Anglophone North West and South West regions, the absence of a genuine political process to address decades-old grievances against the Biya government contributed to the radicalization of the discourse and tactics of Anglophone activists. Since mid-2017, Anglophone separatists have attacked government institutions and threatened, kidnapped, and killed civilians perceived to side with the government.

In 2016 and 2017, government security forces used excessive force against largely peaceful demonstrations organized by members of the country’s Anglophone minority who were calling for increased autonomy for their region. During demonstrations in late 2017, government forces used live ammunition, including from helicopters, against demonstrators and bystanders, killing at least a dozen people and injuring scores. Some individuals detained in the context of the demonstrations were subjected to torture and ill-treatment.

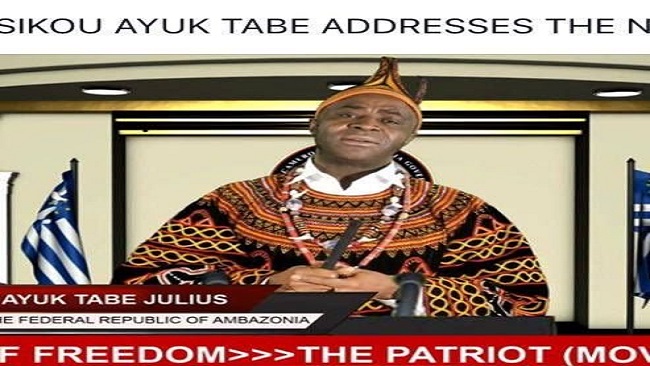

In October 2017, separatist leaders unilaterally declared independence of the North West and South West regions, and the formation of a new nation, Ambazonia. The following month, President Biya announced that Cameroon was under attack from terrorists and vowed to “eradicate these criminals.” The pace and scale of separatists’ attacks against security forces, government workers, and state institutions increased, especially following the arrest and deportation of 47 suspected secessionist activists from Nigeria in January 2018.

Violations by Government Forces

Human Rights Watch found that government forces responded to the growing separatist insurgency by carrying out abusive security operations against communities suspected of supporting secessionist groups. Security forces committed extrajudicial executions, used excessive force against civilians, tortured and abused suspected separatists and other detainees, and burned homes and other property in scores of villages.

During attacks documented by Human Rights Watch, security forces allegedly shot and killed over a dozen civilians, including at least seven people whom witnesses said had intellectual, psychosocial or physical disabilities who did not flee because they were unable or refused to. At least four older women died, burned alive, after security forces set their homes on fire.

Human Rights Watch also documented three cases where security forces detained people suspected of supporting the secessionist cause, and then tortured and killed them in detention. In a fourth case, Human Rights Watch analyzed evidence of torture filmed by perpetrators, who appear to be gendarmes. On September 24 and 27, a total of nine men were allegedly executed by security forces in the town of Buea, according to videos reviewed by Human Rights Watch and a report by the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa, a local nongovernmental organization (NGO).

Abuses by Armed Separatists: Attacks on Students, Teachers and Schools

To enforce boycotts of schools following protests by Anglophone teachers against perceived discrimination by the Francophone-dominated national government, separatist groups attacked and burned dozens of schools, threatened teachers, students and parents, kidnapped principals and violently attacked teachers and students. In March, people believed to be armed separatists attacked a high school dormitory in Widikum, North West region, and shot dead Emmanuel Galega, a student.

The pressure tactics forced the majority of schools to close during the 2016-2017 academic year, and as of May 2018 an estimated 42,500 children were still out of school, according to UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Most schools did not re-open in 2018.

On April 30, Father William Neba, principal of St. Bede’s College, in Ashing near Belo, North West region, was reported abducted while celebrating mass with students. He was released two days later. The school suspended classes on the day of the abduction. In September, unidentified gunmen attacked a girl’s school in Bafut, North West region, kidnapping five pupils and severely wounding the principal.

In September, the government endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, an international political agreement to protect education during armed conflict.

On November 5, up to 78 schoolchildren were reportedly kidnapped in Bamenda, North West region, by unknown gunmen. They were released two days later.

Refugee Rights

Cameroon hosts more than 350,000 refugees and asylum seekers, including 260,000 from the Central African Republic and at least 90,000 from Nigeria. Despite its long history of hosting refugees, Cameroon has forcibly returned tens of thousands of Nigerian asylum seekers since 2015. A 2017 Human Rights Watch report documented how soldiers used violence and abuse, including torture, against asylum seekers in remote border regions. Authorities also imposed unlawful restrictions on movement in Cameroon’s only official camp for Nigerian refugees. In August 2018, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees reported that between January and July, Cameroon unlawfully returned at least 800 refugees and asylum seekers to Nigeria.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Cameroon’s penal code punishes “sexual relations between persons of the same sex” with up to five years in prison. Police and gendarmes continued to carry out arrests and harassment of people they believe to be lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT). In April, police arrested four activists and a security guard at the office of AJO, an organization that works on HIV education with men who have sex with men (MSM), and other vulnerable groups. They spent a week in jail on spurious homosexuality charges before a lawyer secured their release. Cameroonian human rights organizations documented the arrest of at least 25 other men and at least two women on homosexuality charges in the first half of 2018. They also reported numerous cases of physical violence by private citizens targeting LGBT people.

Justice and Accountability

While the government has repeatedly promised to investigate crimes committed by security forces, it has not done so transparently or systematically.

Government officials told Human Rights Watch in June that while they conducted investigations, they did not want to make them public to avoid undermining the morale of government troops. However, the visible lack of accountability appears to have fueled abuses, like arson and torture, rather than ending them.

In July, the government finally granted access to ten Anglophone leaders who had been detained and deported from Nigeria to Cameroon in January. The individuals, held incommunicado for over six months, were permitted to meet their lawyers and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The government dismissed video footage that emerged in July showing two women and two children being executed by men in uniform in Cameroon’s Far North as “fake news.” Only after an investigation conducted by Amnesty International demonstrated the killings took place in Cameroon did the government announce it had arrested six soldiers suspected of executing the civilians in the video.

Key International Actors

France, the United States, and the United Kingdom are Cameroon’s principal partners, primarily in the context of the counter Boko Haram operations in the country’s Far North region. Both France and the US provide Cameroon with military and security assistance and training.

The US and the UK are the only close allies of Cameroon to have voiced public concern regarding the ongoing situation in the Anglophone regions. The US has continued to provide military aid to Cameroon.

In February, the European Union called for proportionate use of force and accountability for abuses in the Anglophone region.

In September 2018, as the pace and scope of abuses continued to escalate in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions, the UN and African Union issued a joint communiqué calling on the government to facilitate access to humanitarian and human rights organizations and engage in an inclusive dialogue to address the root causes of the crisis.

The UN Security Council in August expressed concern about the situation in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions.

Culled from Human Rights Watch

3, May 2019

Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: How to Get to Talks? 0

After twenty months of clashes, the government and the separatists are both refusing to give ground. Both sides must explore compromise solutions aimed at a level of regional autonomy somewhere between the secession the separatists yearn for and the fake decentralisation proposed by Yaoundé.

What’s new? The conflict in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon is deadlocked. There is no dialogue between Yaoundé and the separatists, who are both refusing to give ground: the government is counting on a military victory and refuses to discuss the form of the state; the separatists demand independence.

Why does it matter? In the last 20 months, the conflict has left 1,850 dead, 530,000 internally displaced and tens of thousands of refugees. The intransigence of the belligerents threatens to generate further violence and prolong the conflict, which neither can win in the short term.

What should be done? Cameroonian and international actors should encourage the two sides to make concessions by threatening to sanction those who stand in the way of dialogue and rewarding the less intransigent. Ending the conflict will eventually require changes in the legal framework for decentralisation to grant greater autonomy to communes and regions.

Executive Summary

Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis is deadlocked. Twenty months of clashes have killed 1,850, displaced 530,000 and led tens of thousands to seek refuge abroad, but the government and the separatists are sticking to their irreconcilable positions. The separatists continue to dream that independence is just around the corner. In Yaoundé, the government still wrongly believes it can win a quick military victory. Meanwhile, moderates and federalists, who enjoy majority support, are unable to organise. To break the deadlock, Cameroonian and international actors should put pressure on the government and the separatists. Both sides must explore compromise solutions aimed at a level of regional autonomy somewhere between the secession desired by the separatists and the fake decentralisation proposed by Yaoundé.

The socio-political crisis that began in October 2016 in the Anglophone Northwest and Southwest regions mutated into armed conflict at the end of 2017. Seven armed militias are currently in positions of strength in most rural areas. The security forces reacted slowly, but since mid-2018 have inflicted casualties on the separatists. They have not been able, however, to regain full control over rural areas nor prevent repeated separatist attacks in the towns.

There is currently no dialogue between Yaoundé and the separatists. The latter are calling for talks to hammer out the practical details of independence in the presence of an international mediator. The government refuses to discuss the form of the state or reform of institutions. It proposes instead a decentralisation model that grants neither adequate funding nor sufficient powers to local authorities (communes and regions) and intends to organise the country’s first regional elections later this year. Far from resolving the conflict, this half-baked proposal risks provoking further violence.

Local initiatives to promote dialogue are emerging. In July 2018, Anglophone religious leaders (Catholic, Protestant and Muslim) announced a plan to hold an Anglophone General Conference as a first step toward an inclusive national dialogue. A majority of Anglophones are in favour of this initiative. Initially reluctant, some separatists now seem to be more open to the idea on condition that it prepares the way for a referendum on self-determination that would give the choice between federalism and independence. Faced with opposition from the government, the conference organisers have already had to postpone it twice: from August to November 2018 and then to March 2019. It still has not taken place.

Although some separatists will refuse to give ground, others might accept a dialogue with the Cameroonian authorities, in the presence of an international mediator, to discuss federalism or genuine decentralisation that would grant autonomy and adequate funding to the regions and that would guarantee respect for the specific features of the Anglophone judicial and education systems. Similarly, although the Cameroonian government seems to rule out federalism, it might consent to regionalism or genuine decentralisation, which would involve changes to the legislative framework.

To clear the path to talks, the belligerents must each make concessions in order to establish a minimum degree of trust and reverse the spiral of violence. The government should support an Anglophone General Conference in order for Anglophones to appoint representatives to a national dialogue while at the same time providing non-separatist Anglophones with the opportunity to express their point of view. Cameroon’s president should adopt a conciliatory stance and recognise the existence of the Anglophone problem and the legitimacy of the Anglophones’ demands; order investigations into abuses by the security forces; make provision for reparations to victims and the reconstruction of affected areas; and release the hundreds of Anglophone activists currently in detention, including important members of the separatist movement. The separatists should renounce their strategy of Monday “ghost towns” (general strikes) and their school boycott and expel combatants guilty of abuses against civilians.

A combination of internal and international pressures could lead both the government and the separatists to make such concessions. International actors could reward the parties who agree to moderate their positions and sanction those who remain intransigent. The Europeans and Americans, in particular, should consider targeted sanctions against government leaders and senior army officers who continue to obstruct dialogue (travel bans, asset freeze) and separatists who encourage or organise violence (judicial proceedings). The International Criminal Court prosecutor should open preliminary examinations into abuses committed by both sides, to underline that the pursuit of violence will have judicial consequences. International actors are divided, however, on what position to adopt and what measures to take and should first reach a common position, at least among Western countries.

Internally, Cameroonian Francophones and Anglophones who advocate compromise should mobilise to put pressure on the separatists and the government. In particular, federalists should work together to strengthen their position in the talks. They should continue to dialogue with the separatists and encourage them to moderate their positions, and increase the pressure on the authorities to open up to the less intransigent separatists. Finally, they should conduct an international campaign to promote peaceful solutions.

Once trust has been established, preliminary talks between government, federalist and separatist representatives will be necessary. These should take place outside the country. During this process, international actors, especially the U.S., Switzerland, the Vatican, the UN, the EU (especially France, Germany and the UK) and the African Union (AU) should continue to encourage the government to dialogue and offer funding and support for the talks.

In the event of a dialogue taking place, they could also help to fund compensation payments to victims of abuses, the reconstruction of Anglophone regions, the return of refugees and internally displaced persons and the disarmament and demobilisation of former combatants. Given the level of acrimony between the parties, the presence of an international mediator will be necessary during the preparatory discussions and then during the national dialogue. Several countries and international institutions and organisations have offered to mediate since the start of the conflict. The UN, the AU, the Catholic Church and Switzerland seem best placed to play this role, because the parties to the conflict perceive them as relatively neutral.

Substantive talks between the three parties should take place in Cameroon, which would require the government to guarantee safe passage for separatist representatives. During these talks, the government should indicate its readiness to amend the Constitution in order to grant greater autonomy to the regions and develop the legal framework for decentralisation. This could include direct elections for the regional councils and these councils’ presidents; the establishment of regional structures with substantial financial and administrative power; and an increase in the powers and resources allocated to communes. The government could also reform institutions and governance in order to take account of the specific features of the educational and judicial systems in the Anglophone regions.

More broadly, the conflict highlights the shortcomings of Cameroon’s centralised governance model and raises two crucial issues that the government must address: the need to improve the way the state handles minority rights, colonial heritages and cultural specificities; and the need for a fairer and more equitable redistribution of the country’s wealth. A lasting solution to the conflict requires dialogue and consensus, which are indispensable to undertake the institutional and governance reforms that Cameroon needs.

Source: International Crisis Group