Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

28, March 2020

Boko Haram attacks in northern Cameroon continue unabated 0

While the attention of the authorities and the international community has shifted to the Anglophone Cameroon, attacks perpretrated by Boko Haram have resumed in the far north of the country.

As dawn broke, Akhada set to work.

Huddled on a small chair, he has been sorting the millet grains from the sack placed near him for two weeks. One by one, he eliminates those that are burnt. This is all he has been able to save from his last harvest since a fire ravaged his house on 13 February.

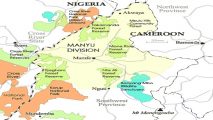

On that day, members of the Boko Haram jihadist group burst into his village of Kilda, a town not far from Koza in the far north region. Houses, crops, and livestock were consumed by the fury of the flames.

Villagers were murdered.

“They killed my cousin right in front of me,” he said. He was only passing through the village to visit the family. With his two wives and two children, Akhada took refuge in Ldamtsai, on the outskirts of Mokolo, the capital of Mayo-Tsanaga department. They occupy a 9 m2 room.

Resurgence of violence

In recent months, hundreds of families living in villages near the border with Nigeria have been forced to flee their homes due to renewed violence from Boko Haram. Hidoua, Gochi, Mandaka, Tourou, Kolofata… The list of localities attacked since December 2019 continues to grow. On almost every occasion, arson, looting, kidnapping, and assassinations have been reported.Daily newsletter: join our 100 000 subscribers!Each day, get the essential: 5 things you need to know Sign up Also receive offers from The Africa ReportAlso receive offers from The Africa Report’s partners

On 15 February, Uzal, in Mayo-Moskota, was completely razed to the ground. “Boko Haram arrived that day at around 10 p.m. They stayed for four hours. They burned everything in their path, and when the defence forces arrived, there was nothing left to save,” said a relative of the region’s governor. According to an official report, three people died in the attack.

Every day there are new arrivals in the Mokolo IDP, but many prefer to settle temporarily in the mountains surrounding the town. “Some just want us to store their food in our attics to protect it from the weather and then leave. In the camps, life is even harder,” said Marguerite, the owner of the premises occupied by Akhada and her family.

It’s been a long time since the fight against Boko Haram became a national issue and was the subject of special attention from the international community.

Since the end of 2016, the focus has been instead on the English-speaking crisis.

In the streets of Maroua, the capital of the Far North, life has resumed. Memories of curfews and tank patrols are told in the bars of the Domayo district, where beer and local music are consumed with abandon.

Remote areas

It often appears that the media is less inclined to carry news from this “front” and rather concentrate on the violence that plunges the northwest and southwest regions into mourning week after week.

The stakes, of course, are not the same. There is nothing in common between Boko Haram, which carries out regular but contained attacks in some remote areas, and the separatist demands of the “Ambazonians”.

Journalist Saliou Aminou explained that the remoteness of the north does not help.

“The Far North is far from the decision-making centre,” he said. “And its elites do not always carry the voice of the people as far as Yaoundé.’

“It’s clear that it’s no longer the great effervescence, as it was between 2013 and 2015,” confirmed Yannick Assongmo of the daily Le Jour.

At the time, not a day went by without a daily newspaper headline about the attacks by Boko Haram. But since then, the news has become more diverse. There has been the conflict in the English-speaking area, but also the post-electoral crisis which has focused attention.

Legislatve and municipal elections

“In fact, the question of the fight against Boko Haram was completely avoided during the debates organised in the run-up to the legislative and municipal elections last February,” said Assongmo.

No political party in the running has put it on its agenda or made any proposal to end the crisis. Opposition leader Maurice Kamto, one of the few to have publicly mentioned the resurgence of attacks, has denounced the silence surrounding him, choosing not to take part in the elections.

To justify his boycott, he said he regretted that President Paul Biya “did not consider that the resolution of the humanitarian tragedy caused by the war against Boko Haram was as important as the holding of the elections”.

On the side of the victims, the “passivity of the defence forces” is stressed — this is believed to be one of the reasons for Boko Haram’s return in force. Nico Seni, one of the survivors of the attack on Kolofata, claimed to have called in vain for help during the attack.

“The military told us that they had not received authorization to intervene!” he claimed.

“Last year, when Kilda was attacked, the army stayed with us,” said Akhada. “Boko Haram were afraid and didn’t come back. But this time the military didn’t come [to the village]. The attackers could come back at any moment, that’s why we left.”

Demobilization of soldiers

“When outlaws enter a locality, if the police don’t respond immediately, people will tend to leave the area,” admitted Roger Saffo, the secretary general of the governor’s office.

However, the intensity of the response deployed at the height of the crisis by the Cameroonian defence forces and their allies in the sub-region has substantially decreased.

Security specialist Édouard Épiphane Yogo speaks of the elimination of “certain military posts” in the villages and the “demobilization” of soldiers on the ground.

The Far North is also feeling the effects of the withdrawal of the Chadian military forces that were deployed in neighbouring Nigeria, some 1,200 soldiers, who finally returned home in early January.

Jihadists now have greater freedom to operate on both sides of the border.

Left to fend for themselves

In the absence of any real support from the authorities, the number of vigilance committees, which served as a bulwark against Boko Haram, has also decreased, and those that are still operational have become less effective. For example, in Mogode commune, the local self-defence group now has only about ten members, compared to more than 250 at the peak of the conflict.

To make matters worse, lack of maintenance, rains and mud have filled entire portions of the large trench built in 2017 by the army to block the advance of the jihadists. From now on, the inhabitants of the surrounding villages tell us, it is mainly used as a passageway by the attackers.

However, the Cameroonian authorities refuse to be alarmed.

“Our defence forces are doing a titanic job, and the task is not easy,” insisted Roger Saffo. “The proof: we have been engaged in this fight since 2014 and we haven’t lost one square centimetre of our territory.”

Bottom line: Like many displaced people, Akhada, for his part, hopes for a national surge and large-scale mobilization, as was the case in 2014.

“We don’t have the means to defend ourselves,” he said. “If nothing is done, they will massacre us all!”

Culled from The Africa Report