23, August 2021

Southern Cameroons Crisis: Interim Gov’t statement on killings in Bali and Kumbo 0

Fellow Ambazonians,

On Sunday, 22 August 2021, despicable cruelty was unleashed by the military of French Cameroun upon our people in Presbyterian Church Ntanfoang, Bali, during a service of worship. Eyewitness reports and videos from worshippers confirm that the French Cameroun army randomly attacked and fired at the Church from the windows. A Southern Cameroons Christian, Grace, was massacred at the scene. The Pastor was injured and taken to the local health centre. Our thoughts and prayers are with Grace’s family at this challenging time in the history of our country-The Federal Republic of Ambazonia. The Interim Government wishes all those who sustained injuries during the Bali attack a speedy recovery.

On Friday, 20 August 2021, the French Cameroun army attacked children at St. Theresa School (STS) Kumbo and killed Sinclair Shalanyuy. Sinclair was young and had a bright future ahead of her. Our thoughts are with Sinclair, too, and what’s more? She will never be forgotten!

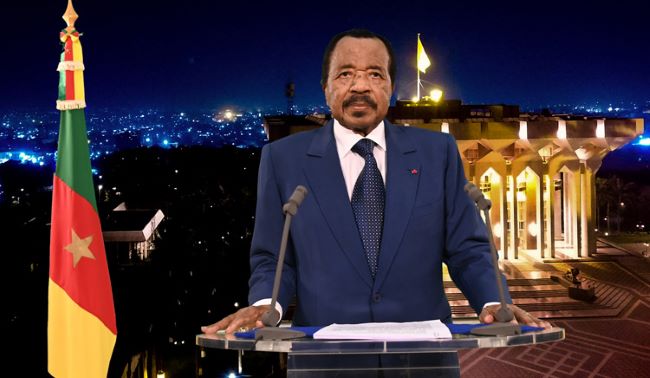

Fellow Southern Cameroonians, these savage attacks perpetrated by soldiers loyal to the Biya French Cameroun regime in Yaoundé on our defenseless civilian population have become endemic. These ongoing crimes against humanity are premeditated and designed to terrorize and traumatize our suffering civilian population. Your Interim Government is presently consulting with Ground Zero commanders, and Southern Cameroons Self Defense Forces shall respond to these unprovoked attacks appropriately.

People of Ambazonia, our fight represents an unyielding rejection of colonialism in any form, shape or manifestation. The rejection is consistent with international law, which gives hope to colonized people struggling for their liberation. History teaches us that many nations have won their liberation battles. Consequently, we shall overcome.

Fellow Ambazonians, we will continue to fight until self-determination is achieved. Be neither discouraged nor distracted. Our time shall come. Grace and Sinclair Shalanyuy, like thousands of Southern Cameroonians, have not died in vain. We owe them a debt to make Ambazonia a reality. Attacks on Churches and Schools underscore how desperate French Cameroun has become. It is a nation that has no respect for human lives and international norms. But we must continue our fight for freedom and justice with the belief that we shall overcome.

We have many long years of struggle and suffering before us as the path we have chosen is full of danger, but it is a path worth taking. The cost of freedom is high, but we must pay the price. As a people, one path we shall never choose is the path of surrender. Our task is simple; we must win and live free or die in the process of freeing ourselves.

Thank you,

God bless the Federal Republic of Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia

Dabney Yerima

27, August 2021

Cameroon alone can’t stop illicit arms flooding into the country 0

The proliferation of illegal arms in Cameroon increases violence and insecurity in a country already grappling with violent extremist attacks and a separatist conflict.

The African Union Commission’s Economic, Social and Cultural Council estimates at least 120 000 small arms and light weapons in illegal circulation in Cameroon, including revolvers, pistols, rifles, assault rifles and machine guns. However the government has granted only 3 800 authorisations to carry small calibre ammunition, according to data provided by Paul Atanga Nji, Minister of Territorial Administration.

On 8 June, Cameroon’s House Speaker of the National Assembly, Cavayé Yéguié Djibril, said illicit weapons held by civilians should be retrieved with urgency amid rising criminality and insecurity.

Evidence suggests a strong link between arms trafficking into Cameroon and an upsurge in crime in the capital Yaoundé and the country’s two Anglophone Northwest and Southwest regions, where there is ongoing insurgency and separatist conflict. Recent increases in Boko Haram attacks on civilians in towns and villages in the Far North are also a factor.

Cameroon and Nigeria have a history of cooperating to combat arms proliferation. These efforts will need to be stepped up in the face of reported advances by the Islamic State in West Africa Province along the borders of Cameroon, Nigeria and Chad. These incursions could increase illegal arms flows into Cameroon.

Conservative estimates by residents in these regions who spoke to the ENACT organised crime project indicate that over 250 footpaths from Nigeria’s Borno, Adamawa and Benue states lead into Cameroon. These tracks are mostly unknown to security forces, including the Multinational Joint Task Force. The routes provide unfettered passage for those smuggling arms into the country.

Cameroon has a long history as a source, transit and destination country for arms trafficking. In September 2013, 5 400 AK-47 rifles were seized in Maroua, the capital of the Northern Region. In January 2014, security forces arrested a man attempting to transport 655 guns to Nigeria. In 2018, the military reportedly raided a warehouse operated by Cameroonian nationals containing a cache of 10 500 rounds of ammunition and an undisclosed number of explosives, guns and cutlasses.

In 2019, Cameroon’s military arrested several men and seized and destroyed 2 500 locally made guns, ammunition and other weapons allegedly being circulated along the northern border with Chad and Nigeria. The illegal weapons were seized from smugglers, hostage takers, poachers and suspected Boko Haram fighters.

Over the past two years, many illicit firearms have been seized from dealers in northern Cameroon coming in from countries experiencing conflicts such as Sudan, Nigeria and Chad, according to a police source in Garoua.

Cameroon has a long history as a source, transit and destination country for arms trafficking

Weapons traffickers in this part of Cameroon include Boko Haram, community militias, separatist rebels and gangs engaging in banditry in the ungoverned border spaces linking Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Chad. Known as the ‘Triangle of Death’, residents are victims of murder, rape, kidnapping and livestock robbery.

The death of Chad’s president Idriss Déby in April 2021 has also raised concerns about increased arms trafficking from Chad into Nigeria and Cameroon. Observers fear for the future stability of Chad’s neighbouring West and Central African states, as Déby’s military provided a bulwark against violent extremist threats in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin.

The government of Cameroon’s multiple approaches and policies to counter arms trafficking and related problems have proven ineffective. A 2016 law made the unlawful possession of a gun in a manner that disturbs the peace or alarms anyone punishable by three months to two years’ imprisonment or a fine.

The military has a major role to play in stemming the flow of arms into the country. However, a shortage of personnel to control the extensive borders that it shares with Nigeria and Chad makes military patrols almost impossible.

Cameroon has made limited resources available for deploying soldiers and police to the unstable north

Cameroon has made only limited resources available for recruiting, training and deploying soldiers and border police to the country’s unstable north. Doing so would enable better surveillance and intelligence. Instead, inaction and corruption in the security sector and among customs officials allow arms to flow uninterrupted through the northern corridors. Police intelligence to identify and track the groups dealing in weapons is also inadequate.

In terms of a regional response, in 2018 Cameroon hosted the first conference of state parties to the Central African Convention for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons. The meeting, known as the Kinshasa Convention, aimed to find solutions to arms trafficking in the region. Given the current dire situation, a review is needed of what has been achieved since the convention was ratified in 2017.

The Multinational Joint Task Force’s efforts to boost border security between Cameroon, Chad and Nigeria are insufficient. A fundamental problem is a lack of resources to recruit, train and support the military and the operational demands of tackling arms trafficking. There is also little evidence of collaboration among defence intelligence units of the three countries.

Stabilising the situation should be a priority for Cameroon. However, it should be handled as part of a plan to invest in human and infrastructural development in the north of the country. Addressing the region’s underlying challenges is essential for long-term stability, which at present seems unattainable.

Source: Issafrica.org