19, February 2021

Of Biya the Cameroonian Jesus Christ and the increase in Yaounde’s Car Fleet in 2021 0

The man responsible for running a prosperous nation to the ground is indeed a blessing to his people and Cameroonians are lucky to have him as their head of state. State radio and television says he indeed a Jesus Christ.

Recently, the Biya Francophone Beti Ewondo regime announced its expenditure on cars which is expected to be made this 2021 in thirty administrative departments.

In spite of the difficult economic situation in the two Cameroons, the Biya administration that only cares about the French Cameroun Kaiser, his acolytes and represents falsehood intends to increase its car fleet in 2021.

Cameroon Concord News Group understands that for the current year, the consortium of crime syndicates in Yaoundé will be spending the sum of FCFA 5,343,285,000 in car purchases.

The Ministry of Territorial Administration comes first with an estimated expenditure of 850 million FCFA. The Prime Minister’s Office (460 million FCFA), the Ministry of Health (416 million FCFA), the Presidency of the Republic (nearly 400 million FCFA), the Ministry of Youth and Civic Education (269 million FCFA), the National Commission for the Promotion of Bilingualism (250 million FCFA), the Ministry of External Relations (246, 4 million FCFA), the Ministry of Economy (211 million FCFA), the Ministry of Commerce (210 million FCFA), the Ministry of Women’s Promotion (193.5 million FCFA), the Ministry of Transport (178 million FCFA), the Ministry of Scientific Research (177 million FCFA), the Supreme Court (153 million FCFA).

The Ministry of Labour (CFAF 125 million), the Ministry of Domains (CFAF 120 million), the Ministry of Mines (CFAF 110 million), the Ministry of Public Procurement (CFAF 114 million), the Ministry of Employment and Professional Training (CFAF 108 million), the Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (CFAF 102 million), the Ministry of Agriculture (CFAF 100 million), the Ministry of Water and Energy (CFAF 100 million), the Constitutional Council (CFAF 90 million), the Ministry of the Civil Service (CFAF 80 million), the Ministry of Tourism and Leisure (CFAF 60 million), the Ministry of the Environment (CFAF 60 million), the National Disarmament Committee (CFAF 60 million), the Ministry of Social Affairs (CFAF 50 million).

In French speaking Cameroun, it is business as usual despite pressure from the European Union, and more recently the Vatican for the 88 year-old Biya to reconcile the country and make peace with the people of Southern Cameroons-Ambazonia.

The Francophone dominated government is still in favour of a military response to the crisis in Southern Cameroons and nobody not even the Holy Father Pope Francis has succeeded to talk President Biya out of the madness and cruelty he has brought to a once prosperous nation.

Buying of expensive cars and handing them to senior regime officials both in government and in the military and above all, having superior military power, will still not put an end to the Ambazonia resistance because the determination of eight million Southern Cameroonians will surely keep the military in the jungles of Southern Cameroons for a very long time.

By Soter Tarh Agbaw-Ebai

1, March 2021

Cameroon: The country is imploding 0

Cameroon has been touted as an oasis of peace in a desert of chaos for many decades, but for some time now, the country has gradually been ranking itself among the most dangerous, corrupt and chaotic countries to live in as dissent and frustration spread across the country like wildfire.

Four years ago, the country’s president, Paul Biya, erroneously declared war on the country’s English-speaking minority which was simply demonstrating to bring its sorry plight to the attention of the government and the international community and what Mr. Biya and his collaborators thought would be wrapped up in a week has now lasted four years with more than 7,000 young Cameroonians already sent to an early grave in a war that has no raison d’etre.

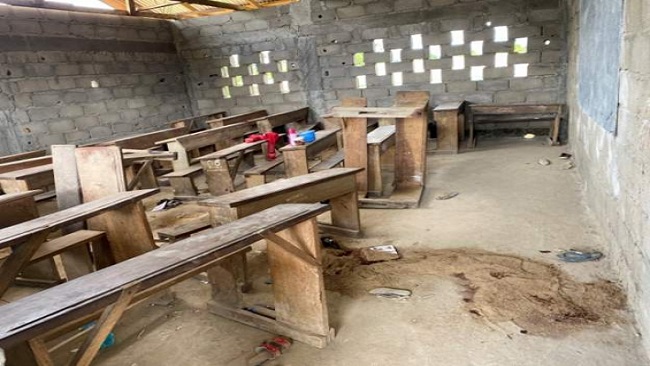

As the government and militia have transformed the country into an open air killing field, the country’s economy has taken a nosedive, with millions of Cameroonians seeking employment and thousands losing their jobs in the country’s two English-speaking regions where the killings are going on unabated.

The number of internally displaced person has continued to swell, while millions have fled to neighboring Nigeria where they are living rough and waiting for the fighting to end for them to return to their country, though their homes have been razed by government soldiers who are wont to inflicting collective punishment on the population each time an army soldier is killed.

But it is not only Southern Cameroons that is going through such an apocalypse. The northern part of the country has been the theater of violent confrontations between government troops and Boko Haram fighters who have bombed many civilians into an early grave.

While the government has been active in the North hoping that it could roll back Boko Haram fighters who are believed to come from Nigeria, government forces have succeeded to alienate Northerner due to massive and bloody killings and abuse of the civilian population which now sympathizes with Boko Haram fighters who are sometimes viewed as liberators.

Noted for its corruption, the government has never really sought to address those issues that are really threatening national unity and integration. The North, like many parts of the country, has been neglected, with very little development projects being implemented in that part of the country.

Tribalism and nepotism are really tearing the country apart as most senior government positions are only occupied by the president’s tribesmen and those loyal to him and his ruling crime syndicate known as the CPDM.

However, it is not the government’s nepotism that is the issue but the results it has posted over the last four decades. Cameroonians would not be bothered if those occupying those strategic positions were really delivering desired results.

While across the country the unemployment rate is high, it is a lot higher in the northern region of the country where there are no companies, no roads, no hospitals and no social services and financial assistance that can even cushion the impact of the economic hardship.

The frustrations in the North are legion and the pain is excruciating. The North has lost almost everything it had during the Amadou Ahidjo days and this is really painful.

Northerners have grudges and they want to get their pound of flesh sooner rather than later. The Biya regime had killed thousands of Northerners, especially senior northern military officials, following a coup d’état in 1984 that led to the country’s first president, Amadou Ahidjo, fleeing to Senegal where he died and is currently lying in an unmarked grave.

This bitterness and the corruption which have robbed the northern population of many services has pushed the frustrated northern population to set up a militia which is now armed and willing to fight the Yaounde government that has never incorporated dialogue into its national development and integration strategy.

The new militia is enjoying huge support from muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, Quatar, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates which surely have a hidden agenda that may result in the long term destabilization of the country.

Cameroon is falling apart and the way things are shaping up, if care is not taken, it might end up like Zaire, currently the Democratic Republic of Congo, where since its brutal dictator, Mobutu Seseseko, fell in 1994, the country has been unstable and the number of militia has grown by leaps and bounds and the country has become the epitome of political chaos.

The international community must stop looking the other way as Cameroon continues its unfortunate but sure descend to the bottom of the abyss of chaos and corruption.

With new armed groups cropping up on a daily basis, it is obvious that the country which is now on life support may one day implode and the consequences could linger for a very long time.

By Soter Tarh Agbaw-Ebai