27, September 2018

Why video evidence should not be the only thing that forces the Biya regime to investigate human rights violations 0

On July 12, Amnesty International released a detailed analysis in response to the emergence on the internet of a video depicting the execution of two women and very young children by Cameroonian armed forces. One of the children was killed strapped to a woman’s back, each executed by the same deadly hail of bullets.

The horror depicted in the recordings hit the international headlines, and the government immediately replied, dismissing the video as “fake” and designed to “tarnish the image of Cameroon’s defense forces.” Eventually, the government promised to look into the video and reported later on having arrested seven soldiers in connection with the event.

Less than a month later, another video came to the attention of Amnesty researchers, this one depicting a “kamikaze” reprisal mission, as jokingly described in the recording by one of the soldiers. The video documents the movement of soldiers on foot and vehicles through a village. Midway through the recording, with structures burning in the background, we witness the execution of a dozen people, sitting and laying against an exterior wall.

Then too, Amnesty released a statement condemning the executions carried out by Cameroonian armed forces. This time, rather than immediately dismissing the newly emerged video as fake, the Minister of Communications said the government would open an investigation, though at the same time claiming the government was facing a “campaign of denigration.”

As human rights investigators increasingly handle video and photographic evidence in the course of their work, the methods used to authenticate the “who, what, where, and when” of these materials have become more and more sophisticated. This authentication work is crucial as it is not uncommon for video or other material to be “fake” — staged, manipulated, edited or — quite frequently — from somewhere else.

Sometimes, it is material misattributed from another place or time. Or it may be a piece of content may show something, but whether it is evidence of a human rights abuse is ambiguous. Like other types of evidence, video and photographic material whose origin or history is unclear is treated with the rightful skepticism by investigators, precisely because misinformation is increasingly manifesting in visual form.

How we authenticated

In the case of the two recent Cameroon videos, the “what” is undeniable — the unambiguous executions of unarmed men, women, and children.

As to who the perpetrators are in the videos. Amnesty International investigators visually identified uniforms, weapons, other equipment, and military ranks, and were all known to be associated with, or belong to, Cameroonian security forces. In one of the videos, identification of the Zastava M21, an automatic rifle that is rare in Africa but used by a small section of the Cameroonian army, was an important clue. Analysis of the audio dialogue — accents and local languages spoken — was consistent with visual findings, and there can be little doubt that in both videos, the Cameroonian security forces were direct participants in the crimes recorded.

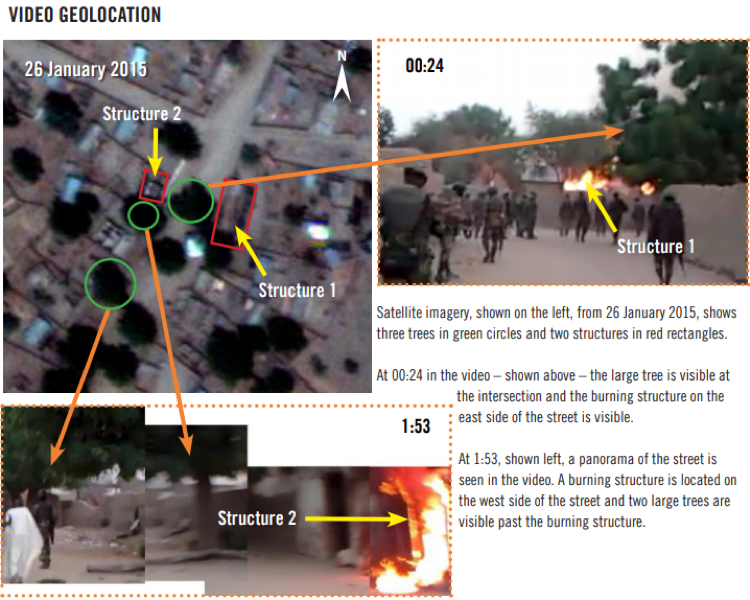

As to when and where the videos were taken, it is more generally difficult to conclude either with certainty without some knowledge of the other. In the case of the most recently released video, investigators identified possible locations through verbal cues in the recording and review by local contacts. Importantly for corroboration, the person recording the video walked for some distance while filming. This allowed analysts to identify many visual cues in the video — road intersections, oddly shaped buildings, trees, among others — as well as their spatial relation to each other.

Analysts at Bellingcat — a collective of online investigators using open source and social media — also working to locate the video — identified a possible location: the village of Achigachia. To independently verify the location, Amnesty investigators took the visual cues taken from the video and plotted against satellite imagery of Achigachia to determine if there was a perfect overlap. There was, including at the exact coordinates in the village where at least 12 people were executed against a wall by a barrage of automatic gunfire. In a longer version of the same video, which surfaced later, the soldiers themselves named the village where the events occurred.

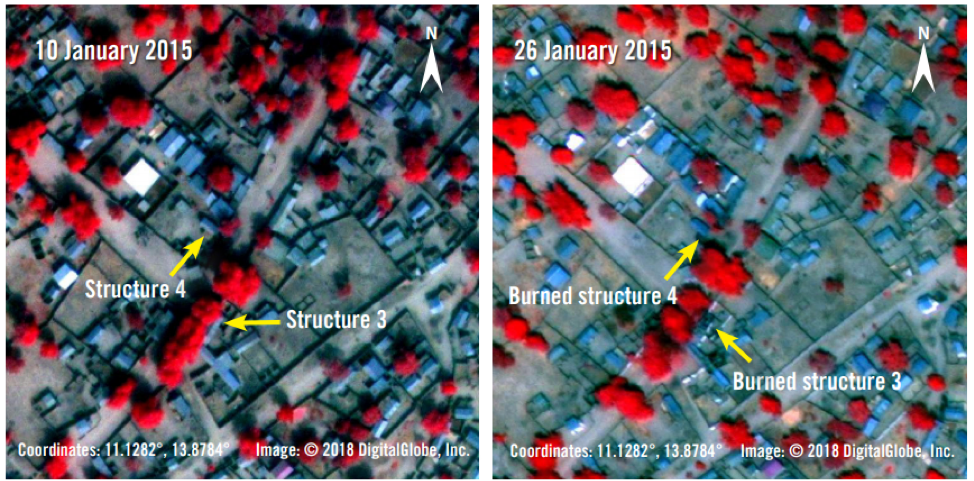

With the confirmation of where the executions took place, the question became whether we could narrow the time in which the crime occurred. With no references to the date, season, or even the year in the video or audio, investigators again relied on satellite imagery. Since the “kamikaze” mission documented in the video included the burning of buildings, an Amnesty satellite imagery expert scanned imagery archives of the town to determine whether burning was evident at those precise points. With luck, two images taken close in time to each other in January 2015 captured the town before fires, and after.

Thus, through careful and detailed analysis, we concluded that the second video was taken in Achigaya between 10 and 26 January 2015 and depicts extrajudicial executions at the hands of Cameroonian security forces.

Why the videos should not have mattered more than previous violations

In today’s media-saturated world, one of the most notable characteristics about these recordings — aside from the uniquely horrifying events they document — is when they were captured. These videos did not capture breaking events. They are both years old.

In response to the video of the execution of the women and children, the UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights stated:

“The government of Cameroon has an obligation to investigate this atrocious crime urgently…I am deeply worried that these killings captured on camera may not be isolated cases.”

Indeed, they are not isolated cases, and in most respects, the videos do not reveal an unknown pattern. In September 2015 and again in July 2016, Amnesty issued extensive reports documenting widespread abuses by Cameroon’s security forces in the course of their fight against Boko Haram: arbitrary detention, torture, disappearances, and the killing of civilians.

Over the last 2 years, Amnesty has continued documenting abuses amounting to war crimes by the Cameroonian security forces operating in the Far North and elsewhere. Just as the crimes depicted in the videos are unambiguous, so too are the crimes documented by Amnesty and others over the intervening years since they were first recorded.

While it is not uncommon for additional evidence to emerge after a report publication, this instance is notable because of the attention received in news media, likely a result of the abject cruelty the videos depict. While the government has made initial statements at least paying lip-service to accountability, it should not come only in response to the emergence of video, 3 years after the fact.

While video evidence can be a powerful tool for human rights defenders, and digital connectivity is empowering ever-larger segments of humanity to document the struggles they face, there is a risk. Video documentation cannot become the minimum evidentiary standard that compels governments and authorities to act in the face of abuses by police or security forces.

The absence of a meaningful response by authorities to these horrific acts is part of a larger pattern of unwillingness or inability to hold the perpetrators to account in Cameroon’s fight against Boko Haram. Such an atmosphere of impunity causes the horrific acts witnessed on the videos and documented in extensive reporting. And it leads to equally horrific acts that are not captured in video and will never similarly capture the attention of news media and the broader public.

Scott Edwards is a Senior Crisis Adviser at Amnesty International based in Washington DC.

Looking at this flyer attached to this report, one must wonder what French President Emmanuel Macron will do if by some strange happenstance, Biya is not the president of Cameroon after October 7. Must Biya’s picture be included in the flyer? Will Macron still chair this forum with Akere Muna or Joshua Osih as president? Probably, Macron knows Biya will be president because in Cameroon, you cannot organize elections and lose.

Looking at this flyer attached to this report, one must wonder what French President Emmanuel Macron will do if by some strange happenstance, Biya is not the president of Cameroon after October 7. Must Biya’s picture be included in the flyer? Will Macron still chair this forum with Akere Muna or Joshua Osih as president? Probably, Macron knows Biya will be president because in Cameroon, you cannot organize elections and lose.

28, September 2018

Southern Cameroons Crisis: Will the Catholic Church Play Peacemaker in Cameroon? 0

Since 2016, Cameroon, the West African state most famous for its soccer prowess, has descended into conflict. With the country voting in an already discredited presidential election on 7 October, the need for strong leadership from the Catholic Church has never been greater.

The roots of the conflict

Cameroon’s English-speaking minority claims it has been increasingly marginalized by the Francophone majority since gaining independence. Of 32 cabinet members, only one is Anglophone, even though English speakers represent 20% of the population. In 2016, the government tried to impose Francophone judges in the Anglophone region’s courts, and to force the French language on its schools. This led to peaceful civil protests such as strike days when shops and schools closed. The authorities responded with disproportionate force, inadvertently fueling a militant secessionist movement. An example of this heavy-handed reaction, as reported by the impartial human rights watchdog, Crisis Group, was a government helicopter hovering over a church, shooting unarmed worshippers as they emerged.

The conflict deepens

The security situation is deteriorating rapidly. Dozens of secessionist leaders who were detained in January remain incommunicado, adding to Anglophone grievance. A recent Amnesty report describes the army’s scorched earth tactics, with 106 villages in the North West and South West regions raided, looted, and burned. Their ethnic cleansing strategy is working: 200,000 have fled into the bush, while 20,000 are in refugee camps in Nigeria.

Social media heightens the sense that English-speakers are being persecuted. Stories of government soldiers torturing and humiliating Anglophones are common, as are disturbing videos of human rights violations circulating online. In this tense atmosphere, there are rumours that political prisoners are being sprayed with chemicals that make them unwell. Cameroon authorities have reportedly denied visas to the International Committee of the Red Cross. On September 10th, soldiers demanded that doctors at Bamenda hospital hand over wounded patients, suspecting them of being rebels, rather than civilians caught in cross fire. There are also unconfirmed reports from the Africa-based Centre for Human Rights and Democracy that the government now requires Anglophones to have internal travel permits. Amnesty estimates 400 people have been killed, although sources in Cameroon believe the figure is much higher, claiming that there are mass graves in the bush.

The authorities’ harsh response to early peaceful protests has led to a polarization of opinion within the besieged Anglophone community. Secessionists are now using extreme violence, targeting security services and government representatives, and punishing civilians who fail to back their vision of a new independent Anglophone country called Ambazonia. Schools not participating in the general strike are being attacked, with 70 torched since 2016. Teachers and students have been seized, and parents are withdrawing their children from schools. The principals of several secondary schools have been kidnapped as retribution for keeping schools open. On an anecdotal level, a Catholic nun reports to your correspondent that her town is surrounded by forces from both sides, effectively holding civilians hostage; people who have fled to camps fear imminent attack; and members of the Diaspora worry constantly about the safety of their family back in Cameroon.

Although the Anglophone Diaspora has appealed to the UK, its former colonial power, it is clear from answers to Parliamentary questions from Lord Alton among others that Britain will go no further than appealing for dialogue. In the run up to Brexit, establishing trading relations is a priority; in June, the government announced that UK interests had signed a natural gas deal with Cameroon worth £1.5 billion. Furthermore, the international community is unlikely to apply pressure to Cameroon’s leader, Paul Biya, while his country’s troops are battling the Islamist terrorists, Boko Haram, in the Lake Chad region.

What can the Catholic Church do?

The church commands the respect of all sides of the population; it is seen as a legitimate voice of civil society. From the beginning of the current crisis, Anglophone faith leaders have called for inclusive talks aimed at finding a peaceful, federal approach, devolving some powers to disenfranchised English-speaking regions. These calls were first ignored and then rejected by Biya’s government. As secessionists have adopted increasingly violent means, the Francophone authorities have hardened their position, refusing to negotiate with terrorists.

The 85-year-old Biya will most probably be re-elected in October, after a process that will fail to meet international standards of free and fair elections, as it usually does in Cameroon. Observers fear that the closing days of the election campaign may spark even more violence. Biya, who has been in power since 1982, seems determined to ignore Anglophone calls for dialogue. Meanwhile, it is noticeable that few French-speaking faith leaders have expressed solidarity with their opposite numbers in the Anglophone region, or have put pressure on Biya to compromise.

In November there will be a conference of faith leaders, convened by the Anglophone churches. This is an opportunity for French-speaking Catholics to join moderate Anglophones in calling for inclusive dialogue to resolve the country’s crisis by non-violent, constitutional means. The church is in a unique position, with the moral authority to push the government into negotiations. The continuing disengagement of many Francophone faith leaders is unhelpful at best. While brave Anglophone priests and bishops demonstrate the courage to seek a peaceful and moderate way forward, they deserve the active support of their fellow religious leaders among the French-speaking majority.

Source: Independent Catholic News