3, April 2020

New 4,000-bed coronavirus field hospital opens in London 0

Prince Charles opened a new 4,000-bed temporary hospital in a conference centre in east London on Friday, the first of several being built in Britain to deal with the coronavirus outbreak.

The new state-run National Health Service (NHS) Hospital is named after the trailblazing 19th-century nurse Florence Nightingale and has been built in just nine days.

Queen Elizabeth II’s eldest son and heir officially launched the facility via videolink from Scotland, where he has been in self-isolation after testing positive for COVID-19.

He paid tribute to everyone involved, calling it “quite frankly incredible” to have transformed the giant ExCeL centre into a critical care facility in such a short space of time.

“I was one of the lucky ones to have COVID-19 relatively mildly,” he said. “But for some, it will be a much harder journey.

“I am therefore so relieved that everyone can now have the reassurance that they will receive all the necessary technical care they may need, and every chance to return to a normal life.”

With Nightingale often named “The Lady of the Lamp” and seen as one of the founders of modern nursing, he said the name was appropriate.

“In this dark time, this place will place will be a shining light,” the prince said, but added that he hoped it would not required for long.

NHS Nightingale London will initially take 500 people in the coming days, said Health Secretary Matt Hancock, who has also tested positive for COVID-19.

It will take intensive care patients with COVID-19 from other London hospitals, which have seen the most number of cases across Britain.

– ‘Invisible killer’ –

The size of 10 district general hospitals, the new facility has more than 80 wards, each containing 42 beds, and when fully operational will require more than 16,000 staff to run.

Hancock praised the NHS, a taxpayer funded service free at the point of use, which has been struggling in recent years as a result of public spending cuts.

“In these troubled times, with this invisible killer stalking the whole world, the fact that in this country we have the NHS is even more valuable than before,” he said.

Temporary hospitals are also being built in exhibition centres in the cities of Birmingham and Manchester, with capacity of up to 3,000 beds between them.

A third is under construction in Glasgow and plans are also in place to build two more in Bristol, in western England, and the northern city of Harrogate offering 1,500 beds.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens said he hoped the extra two sites would not be needed.

“That will partly depend on continuing public support for measures to reduce growth in the infection rate by staying at home to save lives,” he said in a statement.

However, health officials say the measures will take time to have an effect and the death toll continues to mount rapidly, reaching 2,921 on Wednesday.

Source: AFP

5, April 2020

Coronavirus deaths rise above 65,000 worldwide as registered cases surpass 1.2 million 0

More than 1,206,480 declared cases have been registered in 190 countries and territories since the epidemic first emerged in China in December. Of these cases, at least 233,300 are now considered recovered.

The tallies, using data collected by AFP offices from national authorities and information from the World Health Organization (WHO), probably reflect only a fraction of the actual number of infections.

Many countries are only testing cases that require hospitalisation.

Italy, which recorded its first coronavirus death at the end of February, has 15,362 fatalities, with 124,632 infections and 20,996 people recovered.

Spain recorded 12,418 fatalities and 130,759 infections, followed by the United States with 8,503 deaths and 312,245 cases — the highest in the world.

France has reported 7,560 deaths and 89,953 infections, followed by Britain (4,313 deaths and 41,903 cases).

China — excluding Hong Kong and Macau — has to date declared 3,329 deaths and 81,669 cases, with 76,964 recoveries.

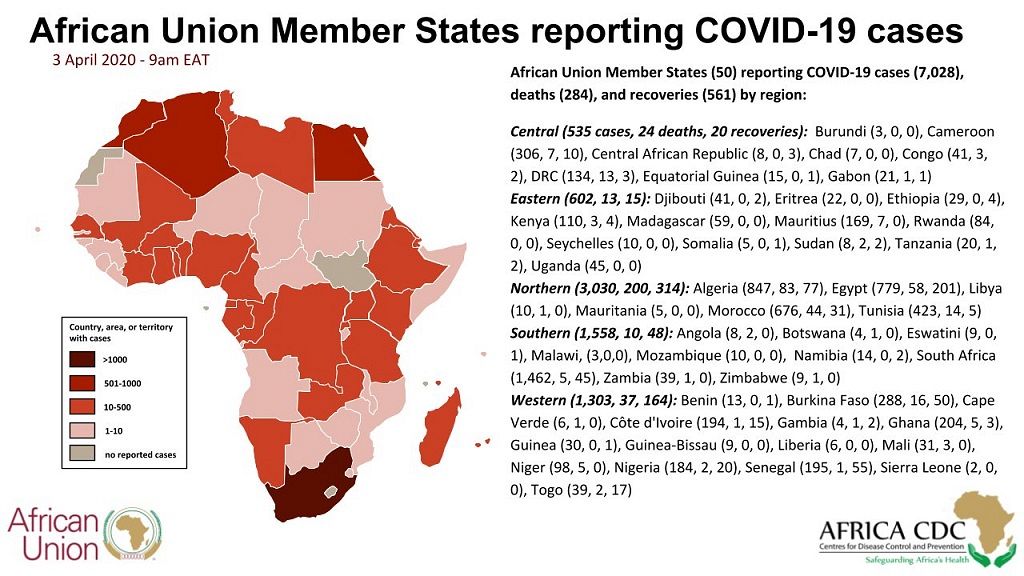

Europe has listed 642,330 cases and 47,093 deaths to date, the US and Canada together have 326,117 cases with 8,747 deaths, Asia 117,571 cases and 4,172 deaths, the Middle East 74,670 cases and 3,779 deaths, Latin America and the Caribbean 30,539 cases with 1,052 deaths, Africa 8,578 cases with 388 deaths and Oceania 6,675 cases with 41 deaths.

Source: AFP