18, March 2019

Should we worry about genocide in Southern Cameroons? 0

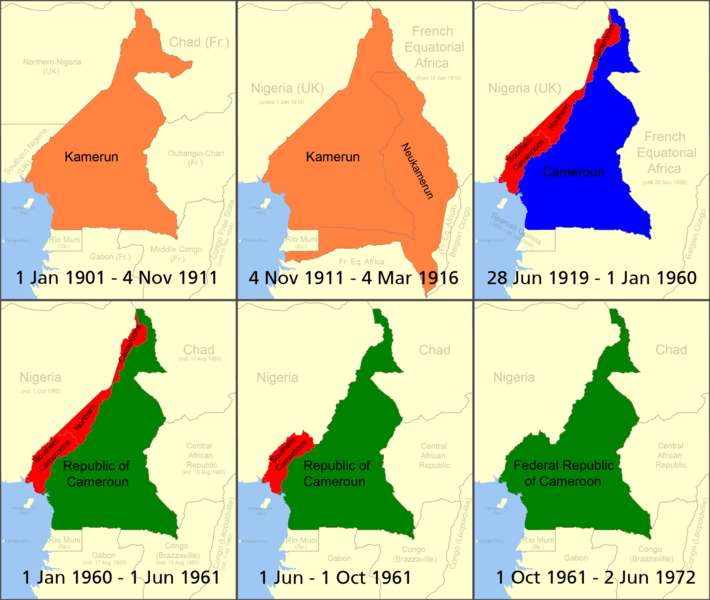

Cameroon has been making headlines as another hot spot of instability in Africa. This time, the conflict is along linguistic and cultural lines, between the Francophone majority in the country, who comprise over 80 percent of the population and dominate politics, administration, education, professions and the military, and the Anglophone minority in the western provinces of Cameroon, who make up little more than 15 percent of the population.

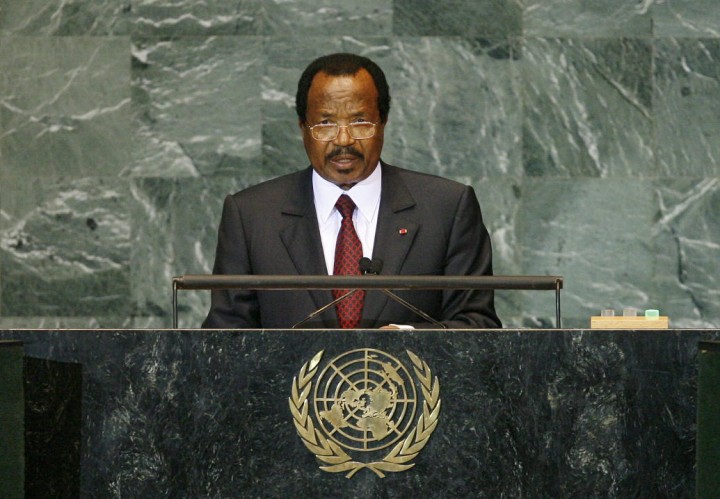

The current conflict began two years ago as a protest by middle-class professionals, predominantly lawyers and educators, against the policies of the Francophone central government, perceived to be further marginalizing English speakers and English-speaking areas. The government of Paul Biya, which has been in power since 1982, believed those initial protests were a challenge to the authority of his regime, and responded with a severe crackdown. This, in turn, led to a full-fledged, generalized secessionist movement among the English speakers in the west.

So far, this is in line with the course of post-colonial African politics. But emerging information from within the country is increasingly setting alarm bells ringing, and the international community needs to monitor the situation very closely.

Initial reports of extrajudicial killings of women and children carried out by the central government army personnel are starting to look like systematic campaigns of violence against civilians, with thousands already dead. Entire villages have been evacuated, as some 500,000 people, well over ten percent of the Anglophone population, have been displaced from their homes as a result of indiscriminate state aggression. And attitudes are only hardening on both sides.

Rwanda’s voices are also echoing in response to these international developments. The situation in Cameroon only started making news after an American citizen was caught in the crossfire and killed. This is despite the fact that the United States has been aware that a good proportion of the documented atrocities seem to have been committed by the Rapid Intervention Battalion, an elite military unit that the US trained to fight Boko Haram in the north of Cameroon.

France, the former colonial power, is taking a stand of wilful ignorance that is eerily similar to its attitude toward Rwanda in the months leading to that genocide. And nobody else wants to go anywhere near Cameroon, since none of the major international players have strategic interests in the area – and certainly no interests tied to the Anglophone minority.

The Western press is also taking a rather strange stance on this conflict, which they often term a “near-civil war”. But a civil war implies that there is some kind of equivalence of power between the two parties, as if there was any doubt about which side might prevail. This is simply not the case here. No amount of hardened “secessionist insurgents” is going to pose a real threat to the Francophone government, or indeed the Francophone regions. Short of the two sides coming together to agree on some kind of compromise – and at this stage neither is contemplating such a thing – there are exactly two possible outcomes: Either the Biya government decides to just cut the two Anglophone regions loose and carry on with the Francophonie, or it decides to drown the two provinces in blood.

The decision over what happens next rests entirely with the Biya government. So far, there are no international power players interested in pressuring the government in one direction or the other. And at every given opportunity, the government has chosen to escalate the matter.

We may not be talking about genocide this week, but it is squarely pointing in that direction. There is nothing to suggest that the internal dynamics of the crisis, or the conduct of the Biya government, will divert the course of events, or that it will slow down.

Perhaps the best hope for Cameroon at this moment in history is, in fact, the US. The US has some leverage over Cameroon’s government and has already cut some military assistance to the Biya government over the escalating humanitarian crisis. But can we have any faith that the Trump administration will initiate a sufficiently robust policy response to a developing humanitarian crisis? That would be out of character for the administration. And as long as that remains the case, Cameroon’s most likely outcome, tragically, looks like Rwanda.

Source: alarabiya.net

26, March 2019

Southern Cameroons War: Citizens are losing hope that their country can remain united 0

For the past three years, civil strife has been tearing Cameroon apart. New public opinion data from Afrobarometer suggest serious — and widening — rifts in fundamental perceptions and attitudes between the country’s Anglophone and Francophone regions.

A snapshot of Cameroon’s turmoil

For more than half a century after independence in 1960, Cameroon’s Francophone majority (formerly ruled by the French) and Anglophone minority (ex-British colonial subjects) lived in uneasy, but largely peaceful, union.

In 2016, occasional protests against what many English-speaking citizens see as discrimination and exclusion intensified and turned violent. Now, militant Anglophone separatists skirmish with government forces almost daily. Human Rights Watch and other observers have accused both sides of killings, kidnappings and other abuses.

According to the United Nations, the violence has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, including thousands who have fled to neighboring Nigeria. In October, English-speaking Cameroon boycotted the presidential election en masse; Paul Biya, who has held that position since 1982, won — but many observers declared the election marred by irregularities and violence.

How deep is the divide between English- and French-speaking Cameroon?

Pulling farther apart on fundamental questions

Public-opinion data show that the Anglophone and Francophone regions have moved quite far from each other since 2016 on fundamental questions of democracy, trust in the state and national identity.

Afrobarometer has interviewed nationally representative samples of 1,200 adult Cameroonians in 2013, 2015, and May-June 2018, producing results with a margin of error of plus or minus three percentage points at a 95 percent confidence level. We did our analysis based on region, rather than primary language.

Here’s what we found. Most Cameroonians living in Anglophone regions no longer view their country as a functioning democracy. That’s a drastic shift from four years ago — and contrasts sharply with the views of their compatriots in Francophone regions. The proportion of Anglophone residents who consider Cameroon “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems” dropped from more than half (52 percent) in 2015 to just 1 in 8 (12 percent) in 2018. Among those living in Francophone regions, the proportion of those who agree has slowly increased from 36 percent in 2013 to 45 percent, as you can see in the figure below.

Cameroon is a democracy | Anglophone vs. Francophone | Cameroon | 2013-2018

Respondents were asked: In your opinion, how much of a democracy is Cameroon today? The graph shows the percentage who say “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems.” (Mircea Lazar /Mircea Lazar)

Similarly, as you can see in the figure below, satisfaction with the way democracy is working in Cameroon has plummeted among Anglophone citizens, from 43 percent who said they were “fairly” or “very” satisfied in 2015 to just 7 percent in 2018. Among Francophones, meanwhile, satisfaction remains low but fairly steady, at 33 percent.

Satisfied with democracy | Anglophone vs. Francophone | Cameroon | 2013-2018

Respondents were asked: Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in Cameroon? The graph shows the percentage who say “fairly satisfied” or “very satisfied.” (Mircea Lazar/Mircea Lazar)

Fewer than half (45 percent) of Anglophone Cameroonians now say they prefer democracy to any other political system, a sharp drop from 64 percent in 2015. Among Francophones, support for democracy has remained steady at two-thirds, or 66 percent. Popular support for elections as the best way to choose leaders shows a similar pattern.

Political scientists often consider popular trust in the police and the army to be a core indicator of broader support for the state — and so here, too, our survey findings may trouble policymakers. As you can see in the figure below, almost 6 in 10 Anglophone citizens, or 58 percent, say they do not trust the police “at all,” up from 39 percent in 2015 and more than double the proportion of absolute distrust among Francophones, at 24 percent. The divide is even greater when it comes to the army: The proportion of Anglophones who say they don’t trust the military “at all” has nearly tripled since 2015, from 22 percent to 62 percent, compared to just 13 percent of Francophones who say the same thing.

Don’t trust police and army ‘at all’ | Anglophone vs. Francophone | Cameroon | 2013-2018

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The police? The army? The graph shows the percentage who say “not at all.”

Another key indicator of a growing chasm is identity: Do citizens identify more with their nation or with their ethnic group? If it’s the former, a fundamental national unity may exist that can help prevent civil conflict. Until recently, in Cameroon only small minorities — between 6 percent and 12 percent — of both Anglophone and Francophone citizens identified more closely with their ethnic group than with their nation. But as you can see below, since 2015, the proportion of Anglophones who identify more strongly with their ethnic group than their nationality has quadrupled, to almost one-third (31 percent). Among Francophones, the increase was from 7 percent to 13 percent.

Ethnic over national identity | Anglophone vs. Francophone | Cameroon | 2013-2018

Respondents were asked: Let us suppose that you had to choose between being a Cameroonian and being a ________[respondent’s ethnic group]. Which of the following statements best expresses your feelings: I feel only [ethnic group]? I feel more [ethnic group] than Cameroonian? I feel equally Cameroonian and [ethnic group]? I feel more Cameroonian than [ethnic group]? I feel only Cameroonian? The graph shows the percentage who say they feel “only [ethnic group]” or “more [ethnic group] than Cameroonian.. (Mircea Lazar/Mircea Lazar)

The results reveal that Cameroon’s national unity is fragmenting

These growing divides between Anglophone and Francophone Cameroonians suggest that beyond the headlines, some citizens may be starting to abandon a belief in the country’s unity. Despite Cameroon’s long history of individual English and French speakers living peacefully as friends and compatriots, these tears in the national fabric will take both time and skilled and inclusive political leadership to mend.

Culled from The Washington Post