14, December 2019

US: President Trump on brink of impeachment as US House committee approves charges 0

A badly divided House Judiciary Committee voted 23-17 along party lines to approve articles of impeachment charging President Donald Trump with both abusing the power of his office over the Ukraine scandal and obstructing House Democrats’ attempts to investigate him for it.

Trump is expected to become the third US president to be impeached when the full Democratic-led House votes on the charges, likely next week, setting up a trial in the Republican-controlled Senate. The Republicans have shown no signs of wanting to remove Trump from office.

In congressional hearings that have gripped Washington, Democrats have accused the president of endangering the US Constitution, jeopardizing national security and undermining the integrity of the 2020 election by asking Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in a July phone call to investigate former US vice president Joe Biden, Trump’s potential Democratic opponent on voting day next November.

“Today is a solemn and sad day,” said Representative Jerrold Nadler, the committee’s Democratic chairman. “For the third time in a little over a century and a half, the House Judiciary Committee has voted articles of impeachment against the president.”

Republicans have defended Trump and accused Democrats of a politically motivated farce aimed at overturning his surprise 2016 presidential election victory.

“Impeachment is a hoax. It’s a sham,” Trump told reporters at the White House after the committee’s vote. “There was nothing done wrong. To use the power of impeachment for this nonsense is an embarrassment to this country.”

If impeached, Trump will go on trial in the Senate in January, just as the 2020 presidential campaign begins to pickup speed.

Trump has alleged that Biden, a leading candidate for the Democratic nomination for president, was involved in corruption in Ukraine and should be investigated by authorities there, but the president has offered no evidence. Biden has denied any wrongdoing.

Abuse and obstruction charges

The abuse of power charge against Trump also accuses him of freezing nearly $400 million in US security aid to Ukraine and offering a possible White House meeting to Zelenskiy to get him to publicly announce investigations of Biden and his son Hunter, who was on the board of a Ukrainian gas company.

Trump also asked Ukraine to investigate a debunked theory that Ukraine, not Russia, interfered in the 2016 US election.

The obstruction charge against Trump is based on his directives to current and former administration officials such as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo not to cooperate with the impeachment inquiry, even if that meant defying subpoenas.

A senior Democratic aide said the House tentatively plans to hold an impeachment debate next Wednesday ahead of a vote on whether to impeach Trump and send him for trial.

Republicans say the president did nothing improper in his call with Zelenskiy, and that there is no direct evidence he withheld aid or a White House meeting in exchange for a favor. Democrats say Trump stopped top aides from testifying.

Signaling investors’ lack of concern at the political upheaval, US stocks hit fresh record highs on Friday on optimism over a possible trade deal between China and the United States before paring gains.

As the Judiciary Committee was voting, China announced progress and said Beijing would cancel tariffs scheduled to take effect. Trump followed up by tweeting that a trade deal had been reached.

Trump is running for re-election in 2020 in what is expected to be a bitter contest with the Democratic nominee.

Senate trial would follow House vote for impeachment

No US president has been removed as a direct result of impeachment. Republican Richard Nixon resigned before he could be impeached for the Watergate scandal, and Democrats Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton were impeached by the House but not convicted by the Senate.

Twenty Republican senators would have to join all 45 Democrats and two independents who caucus with the Democrats to vote to oust Trump from office.

The trial would be presided over by US Chief Justice John Roberts. The length of the proceedings would depend on whether witnesses were called, a decision that is up to a majority vote in the chamber.

Trump has signaled an interest in calling many witnesses, including Biden and Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, believing a big trial would be good for Republicans.

A lengthy trial would eat up weeks of time shortly before the first Democratic presidential nominating contests in Iowa and New Hampshire.

But influential Republican senators have said they want to keep any trial as short as possible.

“This needs to come to a quick end,” Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham, a Republican who has become a staunch defender of Trump, wrote on Twitter.

Trump said on Friday he was open to either a short or long process in the Senate.

“I’ll do whatever I want … So I’ll do long or short,” he said.

“I wouldn’t mind a long process, because I’d like to see the whistleblower, who’s a fraud,” Trump said, referring to the anonymous intelligence official who set off the House impeachment investigation by raising a flag about Trump’s call with Zelenskiy in a whistleblower complaint.

Source: FRANCE 24 with AP

14, December 2019

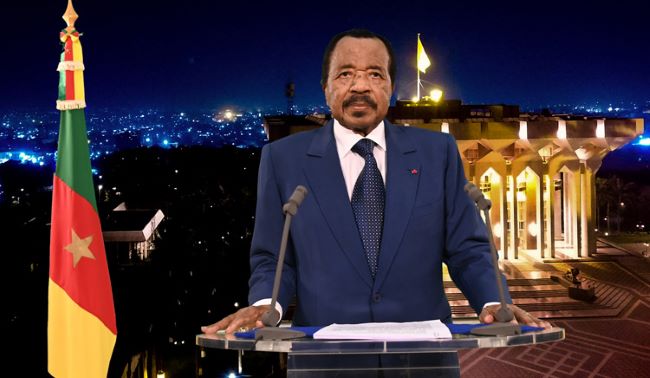

Yaounde: So-called Lawmakers divided over Paul Biya’s Proposal for the Southern Cameroons Crisis 0

Cameroon’s Parliament is divided over the so-called special status President Paul Biya ordered for the country’s English-speaking regions as a solution to the crisis that has killed more than 3,000 people.

Some lawmakers who convened for the extraordinary session of Parliament on Biya’s instructions suggest that only the creation of federal states, one incorporating the country’s English-speaking regions and the other made up of the French-speaking regions, can stop the crisis.

Others said the English-speaking regions’ special status already cedes enough power and resources to the crisis-prone areas, where separatists are fighting to create an English-speaking state

Cavaye Yeguie Djibril, speaker of Cameroon’s National Assembly, told the lower house of the Parliament that Biya asked him to convene the extraordinary session solely to examine the bill and vote it into law because Biya is determined to restore peace in the restive English-speaking regions.

Lawmaker Njume Peter Ambang from the English-speaking South-West said the section of the bill granting a special status to the English-speaking regions could calm rising tensions for peace to return.

“It is a moment for us to leave a legacy and we should look at this particular document with a lot of seriousness and responsibility,” Ambangsaid. “We owe Cameroonians a lot. This is the moment that I think we have to make Cameroonians to know that they elected us for their own interest.”

The bill envisages the creation of assemblies of chiefs, regional assemblies and regional councils for the English-speaking North-West and South-West regions with each of the two regions having elected presidents, vice presidents, secretaries, public affairs management controllers and three commissioners responsible for what the bill describes as economic, health, social, educational, sports and cultural development affairs.

It also would also create the post of a public independent conciliators, responsible for solving disputes over the functioning of regional administrations. The bill also proposes more powers for elected mayors and would give them the authority to recruit hospital staff and teachers.

But lawmaker Henry Kemende, from the English-speaking North-West region, said the special status for the English-speaking regions will not solve the crisis because most English speakers expect the creation of a federal state recognizing the people’s cultural and linguistic diversity. He said the French-speaking regions should constitute one state while the English speakers form another in a federal republic.

“We thought that will have a bill that will admit the fact that we have failed in a unitary state and that we were going to try something different from the unitary state,” he said.

George Elanga Obam, Cameroon’s minister of decentralization, said by opting for the acceleration of decentralization, Biya is respecting proposals made by people his government consulted.

Obam said after consulting Cameroonians of all walks of life and organizing a national dialogue called by Biya, it was unanimously agreed that effective decentralization is the solution to the crisis in the English-speaking North-West and South-West regions. He said the special status will make the English-speaking regions more involved in making decisions that affect their lives and contributing to their own development.

Separatist leaders invited to the national dialogue this fall refused to take part, calling it a non-event. The talks recommended that the English-speaking regions be given special status.

Violence erupted in 2017 in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions when teachers and lawyers protested alleged discrimination at the hands of the French-speaking majority.

Source: VOA