15, May 2020

Readout of Swiss President’s phone call with Paul Biya 0

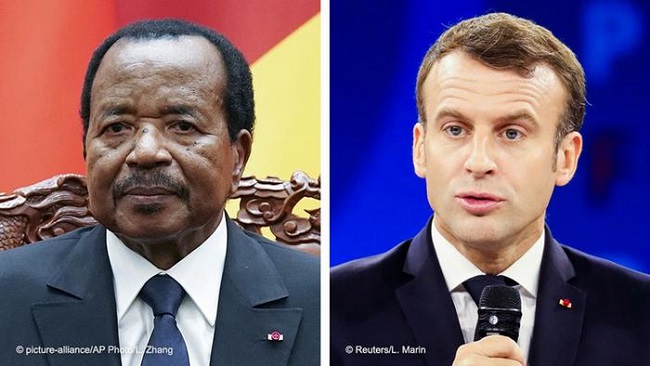

The President of the Swiss Confederation, Mrs Simonetta Sommaruga has said on her Twitter account that she had a telephone conversation with the French Cameroun dictator Paul Biya on the 14th of May 2020 on the crisis in Southern Cameroons and the coronavirus pandemic.

She reiterated to the 88 year-old leader, her country’s willingness to accompany Cameroon in the search for a peaceful solution to the crisis in Southern Cameroons.

“Happy to have had an exchange of views today with President @PR_Paul_BIYA on health and humanitarian cooperation in Cameroon and on Switzerland’s commitment to finding solutions in the North-West and South-West,” the Swiss official tweeted.

Correspondingly, the Swiss government reportedly tried in the past to initiate negotiations between the Cameroonian government and the English-speaking separatists. But the initiative has met with a stone wall from both sides, who are sticking to their positions.

According to NGOs, the war in Southern Cameroons has caused at least 3,000 deaths and more than 700,000 displaced persons and refugees.

By Chi Prudence Asong

15, May 2020

More Americans disapprove Trump’s handling of coronavirus 0

More Americans say they think President Donald Trump is doing a “bad job” handling the coronavirus pandemic and don’t trust him to provide accurate data about the outbreak, according to a new poll.

The CBS News poll found that 57 percent of respondents said they believe Trump is doing a “bad job” handling the public health crisis and 43 percent said the president is doing a “good job.”

Views of Trump’s handling of the outbreak are now 10 points lower than in March, the lowest rating he has received.

The poll also shows 62 percent Americans don’t trust Trump to provide accurate information about the coronavirus or what to do during the outbreak.

Vice President Mike Pence, who leads the White House coronavirus task force, receives similar numbers.

Trump worsening approval rating comes as the number of confirmed infections and deaths from COVID-19 mount.

The pandemic has infected over 1.4 million people in the United States, killed more than 85,000 and devastated the economy.

A whistleblower told a congressional hearing on Thursday that the United States could face “the darkest winter” of recent times if it does not improve its response to the pandemic.

Rick Bright says he was removed by the White House as director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) for raising concerns about the government’s coronavirus preparedness.

BARDA is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services responsible for developing drugs to fight the coronavirus.

Trump, who has been pushing for the US economy to reopen quickly, dismissed Bright as a “disgruntled employee” on Twitter on Thursday morning before the hearing begun.

Source: Presstv