21, December 2019

“Ratzinger and the Future of African Theology” – Motivation and Aspirations: 0

A Panoramic Synthesis

I. Introduction: As I See It

From October 17th to 19th, the Center for Scriptural Exegesis, Philosophy and Doctrine at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake, Mundelein hosted an academic conference on the theme, “Ratzinger and the Future of African Theology,” co-sponsored by the Benedict XVI Institute for Africa. The planners and facilitators of the conference were Dr. Matthew Levering and Fr. Maurice Ashley Agbaw-Ebai. There were over 30 participants at the conference comprising professors and graduate students. Thanks to Fr. Thomas Baima, who, immediately after the conference put out a summary of the events of the conference with a list of participants.[1] What I intend to do in these few pages is to present my reflections on, and a panoramic synthesis of the theological discussions at the conference, while the publication of the papers that were presented is awaited next year.

There is often an air of curiosity and suspicion that surrounds discussions on topics like “Joseph Ratzinger and the Future of African Theology” – bringing together two seemingly incompatible realities: Christianity and the African culture. This suspicion is paralleled in that ancient question asked by the African theologian, Tertullian, albeit in a different context, “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens, the Church with the Academy, the Christian with the heretic? … After Jesus we have no need of speculation, after the Gospel no need of research.” At the heart of this question was the debate regarding the relevance of theological speculations and, to sound anachronistic, the relevance of inculturation in the enterprise of theology. For one thing, the question of philosophy’s relevance in/to theology was considerably put to rest by scholasticism’s espousal of Petrus Damiani’s (1007-1072) dictum, philosophia ancilla theologiae. Since the turn of the twentieth century, however, there emerged a renewed interest in the question of culture and context in the study of theology. This was championed in the works of the Chinese theologian Shoki Coe (1914-1988), amongst others. He is known for the coinage, “contextualizing theology.”[2] This has been carried forward in the works of Stephan Bevans and Robert Schreiter, amongst others.

A remarkable ecclesial moment that signaled the urgency and relevance of “contextual theology” was the Second Vatican Council, which, more than ever before acknowledged the Church’s openness to the world and to cultures, and recognizing theseminaverbi in indigenous cultures.[3] In fact, there is today a growing appreciation of the fact that every theology in the strict sense of the word is “contextual theology,” that is, arising from within a culture and seeking to make sense of the Gospel message in and through the cultural symbols and heritage. This was true of the Greek culture that informed Patristic theology, as it was true of the German culture that informed the theology of the most part of the twentieth century, as it is true today of the African culture, which is increasingly becoming a partner in the knowledge production and meaning making process in theology.

The future of African theology rests on the fidelity of African theologians to the mission entrusted to them, in the words of John Paul II, in Ecclesia in Africa, “It is earnestly to be hoped that theologians in Africa will work out the theology of the Church as Family with all the riches contained in this concept, showing its complementarity with other images of the Church.”[4] This was re-iterated by Benedict XVI (Ratzinger), who reminded Africa’s scholars of their task of studying important theological and social questions for the benefit of the Church and for “developing an African theology.”[5]He further noted, “I express my trust that (African) theologians will continue to probe the depths of the trinitarian mystery and its meaning for everyday African life.”[6]

The foregoing gives us a vivid picture of the motivation of the over 30 scholars who gathered to discuss “The Future of African Theology” in dialogue with the theology of Joseph Ratzinger. With this background, we can fully appreciate the conference discussions, with exciting midpoints, such as the significance of culture and context both for Ratzinger and for African Theologians. Before delving into these discussions, there is one more thing to be cleared. Someone once asked me, “Are you interested in the theology of Ratzinger the theologian or Benedict XVI the pope?” When pushed to extremes, this question betrays the tendency of what I call a “theology without faith commitment.” On the contrary, in Ratzinger, we find a theology that springs from a personal encounter with the saving Logos. Little wonder, prayer plays a heuristic role in his theology, akin to the Eastern hesychast (Palamite) tradition. His method is largely exegetical; and the Fathers, liturgy, the saints, and the magisterium are significant hermeneutical prisms informing his philosophical personalist reflection on the Christian mystery.[7]

II. Presentations and Discussions: Panoramic Synthesis

Rather than follow chronology, I have rearranged the presentations such that they fit in together around particular themes. For a sequence of how the papers were presented, see the following footnote.[8]

The keynote address delivered by Paulinus Odozor was titled, “One and the Same?: Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI and African Theologians on God and God Language in African Christian Theology.”An important nuance clarified here, which shaped all the papers of the conference is that “African Theology” here referred to is in fact “African Christian Theology”. At the core of Odozor’s argument is the claim that there is a continuity between Christianity and its conception of God and the African tradition and its conceptions of God, analogous to the continuity between Christianity and traditional Judaism. The point here is not thatAfrican Traditional Religions (ATR) could hypothetically replace the Old Testament, but that ATR as well as every other indigenous religion (ancient Judaism inclusive, though privileged) share the same God of creation,who discloses himself progressively throughout history. The height of this revelation is Christ Jesus. The “God of Jesus Christ,” that is, the idea of God as revealed by and in Jesus Christ is uniquely new to every culture. [This is strikingly Ratzingerian]. The tensions in the New Testament between Jesus’ idea of God and those of his contemporaries attest to this. Thus understood, ATR,ancient Judaism – despite its privileged place amongst cultures – and every other culture stand in need of God’s unique revelation in Jesus Christ in much the same way. In the light of Christ, every culture/tradition experiences its insufficiency and its need for perfection. Therefore, though the God of ATR is notforeign to the Christian God, yet, the African theologian’s task is to present to the African a clearer picture of the “God of Jesus Christ” in his uniqueness, and how this can influence his/her daily life. Within this framework, Christianity cannot be termed a “European or Western religion”: it stands over and above every culture. The greatest failure of Christianity, therefore, is when it transmits a culture rather than Christ.

Emery de Gaal’s presentation cues in well with the above, as he highlights the Ratzingerian Christo-centrism. He presented on the theme, “Ratzinger on Christ and In/Enculturation.”While tracing the historical development of the Ratzingerian usage of the terms “inculturation” and “interculturality,”de Gaal argues for the indispensable co-relation of culture, Christian mission, and inculturation. For instance, in the Greco-Roman world, by the help of the Holy Spirit, theologians were able to distinguish between philosophical wisdom (adapted into patristic theology) and paganism (which was rejected). I would say, this has become a veritable model for African theologians as they engage the African culture. Culture, de Gaal argues,reveals the human aspiration for the transcendent, though no culture can attain this on its own. Christ is universale concretum et personale, that is, he is the Idea made concrete, personal, and historical.This means Christ is the universally valid in the here and now, the one in whom all persons, cultures, and history participate and find meaning and perfection. Christ does not impact a culture by cancelling it out. Rather, in him a new beginning, a new centre of being is met. In all these shines forth Ratzinger’s Christo-centrism, which further highlights Odozor’s perception of the “Christo-centric” task of the African Theologian’s project.

Paul Adaja’s presentation zoomed in on the primacy of the Logos:“Catholic Theology in 21st Century Africa in the Light of the Primacy of the Logos in the Theology of Joseph Ratzinger.” According to Adaja, in Ratzinger, one finds a personalization of the Heraclitean and Stoic logos. Logos wasunderstood by the stoics as the cosmic principle of intelligence and design. Ratzinger resources this stoic logos and a Johannine appropriation of it. Therefore, for Ratzinger, the logosis at one and the same time the rational principle of creation [reason] and the second divine person of the Trinity, incarnated in Jesus Christ [faith]. Adaja argues that one of the biggest problems of Christianity in Africa is the subtle separation of reason and faith, and he located this problem especially in fanatical Pentecostalism. At the heart of this problem he insists is an anthropological crisis. As a corrective, he proposes that African theologians should focus on the question, “Who is the human person?” while at the same time paying closer attention to the expressions of the human spirit in music, fiction, and other artistic works emerging from Africa. Inferring from Adaja’s claims, it feels safe to conclude that he proposes the logos – principle of reason and faith – incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth as the anthropological paradigm for the African person and humanity at large.

Another presentation that pointing to the anthropological crisis in Africa was that of Joseph Ogbonnaya, on the topic, “Caritas in Veritate and the Challenges to Political Economy of Africa: The Case of Nigeria.”According to Ogboyanna, the anthropological crisis in Africa accounts for the political and economic meltdown in the continent. Enumerating a number of examples from the Nigerian context, he argues that this crisis thrives on a reductionist notion of humanity, which ends up reducing development to the mere accumulation of wealth. Devoid in this process is an ethics of politics or economics. Some fundamental principles of Ratzinger’s Caritas in Veritate, he argues, could provide a corrective. Viz., relationality as key to humanization, the principles of reciprocity and gratuity, solidarity and subsidiarity.

Tegha A. Nji and Valery Akoh’s paper on solidarity could be a good sequel to the above. They presented on the topic, “The African Understanding of Solidarity and the Ratzingerian Concept of Pro-existence.”Hinged on what they call an African communitarian personalism, solidarity for them is characterized by anawareness of that common humanity, the sense of mutual and participative belonging and a shared responsibility towards the welfare of all with whom one belongs, and an esteemed value of sacrificial existence for others.This understanding of solidarity is expressed in the notions of ubuntu and ujamaa, in the African reality of the family and the firstborn son, in the palaver tree model of conflict resolution, and in socio-cultural preverbal and proverbial expressions. While the African ideal understanding of solidarity could be paradigmatic and universally valid, the existential reality in Africa is less perfect than the ideal. They argue that it is only in Christ that the ideal and the praxis of solidarity coincide. This they term the “Christification of solidarity”. This becomes the organizing principle of the dialogue between Ratzinger’s pro-existence – Christ’s solidarity (co-existence) with humanity and existence for humanity even to the point of death – and the African culture – a culture that understands the meaning of existence as being for others. As such, the African understanding of solidarity is a great testament to the seminaverbi found in every culture that Christianity encounters and enriches.

Mary Reginald Anibueze’s presentation espoused the theme of solidarity, in the context of the Eucharist. She presented on the topic, “Benedict XVI and Socio-Communitarian Eucharistic Exigencies: Impact on African and Global Catholicism”Participating in the liturgy, Anibueze argues, should transformthe participants into what they celebrate. In her reading of Ratzinger, she further notes that in the liturgy, especially at communion Christ unifies the faithful to himself and to one another. This underscores the need for actualized liturgical celebrations accustomed to different cultures, which will in turn facilitate full, active, and conscious participation, according to the demands of Sacrosanctum Concilium.She expresses a reservation on how, in praxis, Ratzinger was open to the inculturation of the liturgy, quoting his reluctance to approve local liturgical rites or to participate in them, a case in point being the Zairian rite. This signals more work for African liturgists and theologians, she posits. The social implication of a well celebrated liturgy, according to her, is the transformation of the society: tearing down walls of injustice, hatred, terrorism, corruption, and fostering justice, love, unity, and peace. In the end, the practical question facing Africa and its theologians is this, “What is the appropriate response to poverty, violence and other social ills based on a Eucharistic framework?”

The Liturgy is by far the most exploited area of (African) theology in terms of inculturation. There was another presentation on the liturgy from Joseph Lugalambi, on the topic, “Lex Orandi Lex Credendi: Ratzinger on African Liturgy.”Central to Lugalambi’s reading of Ratzinger vis-à-vis liturgical inculturation is the prescription that the task of inculturation oughtto appreciate the fact that liturgy is indeed true liturgy when it is beyond the manipulation of those engaged in it. He insists on the revealed nature of liturgy as opposed to a human invention. We can fittingly worship God, he paraphrases Ratzinger, only how he reveals himself to be worshipped. In Lugalambi’s reading, Ratzinger likens most post-Vatican II creativity in the liturgy to the Israelites’ apostasy (worship of the molten calf). The problem here, he adds, is the exaggerated quest to make God intelligible that ends up in idolatry. A humanly created liturgy does not draw man up to God but seeks to draw God down to man. For Lugalambi, the challenge facing African theologians, especially liturgists, is to remain docile to the prompting of the Holy Spirit who is the principal agent of inculturation. For the telos of the liturgy is the worship of God and not the glorification of man.

Away from liturgical inculturation,there was a presentation by Dennis Kasule that touched on the political implications of evangelization in Africa. He presented on the topic, “Benedict XVI and the New Evangelization in Africa.” Kasule brings together in a paradoxical tension two images of Africa in the thought of Benedict XVI, viz., Africa as the spiritual lung for humanity in a crisis of faith and hope, and Africa as the Victim of robbers abandoned to suffer. In addition to explicating the implications of the above tension, he summed up Ratzinger’s proposal to Africa’s evangelizers and theologians as follows: to preach Christ and not to get entangled in political and social strives. The basis of this recommendation is Christ himself, whose was not a political revolution but a revolution of love. In the final analysis, from a Ugandan background, Kasuleseeks to answer the question, “Does Benedict XVI’s prescription for a revolution of love answer Africa’s challenges vis-à-vis the inculturation of the Gospel in its socio-political framework?” He leaves this as an open-ended question, with divergent views on either side of the debate.

This question is taken up in profound depth in the paper that was presented by Maurice Ashley Agbaw-Ebai, on the topic,“Joseph Ratzinger’s Theological Reading of Political Power: Relevance for the Continent of Africa in the 21st Century.”In this reading of the political landscape of Africa, Agbaw-Ebai presents Africa as the victim of political and economic injustice both of the West and of her own corrupt political stooges. The poverty of Africa has its roots in a politics separated from truth.Agbaw-Ebai affirms Ratzinger’s stance that the Church’s role is not to dictate political systems to political powers.Christianity has never sought to establish a theocracy, maintains Ratzinger. On the contrary, Christianity, with the initial rapprochement that it found with Greek philosophy, has always pointed to Natural Law and Reason as the basis for political engagement. Christianity takes this path, conscious of the inherent openness of Natural Law to Divine Law. At the heart of what I may call Ratzinger’s “political theology,”therefore, is, in Agbaw-Ebai’s reading of Ratzinger, the claim that good politics and governance is rooted in reason and natural law. Wisdom, therefore, after the example of King Solomon’s prayer, becomes the paradigm for good politics. Ratzinger warns against political messianism, striving on the false hopes that political powers or systems could satisfy the deepest longings of the human person, whereas in fact, God alone can. Recognizing that political ethnicism which promotes and breeds on a perverted notion of solidarity, on individualism and clique-interest, Ebai proposes Ratzinger’s ecclesiology of communion as a corrective.

In the face of the challenges facing Africa and the arduous task of the African theologian, Christopher Collins’ presentation offers a what I may call a Ratzingerian optimism. He presented on the topic, “Joseph Ratzinger’s Confidence in Salvation History.” Collins highlights Ratzinger’s own lived experience of violence in Nazi Germany and his more recent resignation from the papacy as respectively a formation ground and an instantiation of his confidence in a God who works in history. Ratzinger’s thoughts are shaped by a strong confidence in history as the unfolding of God’s plan and the salvific action of the Holy Spirit in that history. For Ratzinger, humanity is invited into a history that is ongoing and living, the history of salvation, the history of God’s word taking flesh in culture. Borrowing from John Allen, Collins articulates Benedict’s liberation theology in terms of the supernatural ground as the deepest and greatest level of existence and the precedence of individual transformation over social transformation. Consequential of this is the fact that a choice between supernatural happiness and present happiness in this world is a false dichotomy, for if meaning does not come from outside of us, it does not ground us.

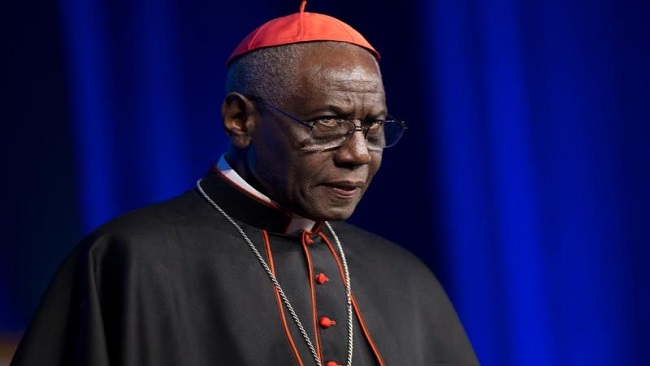

This note of optimism is re-echoed in Jacob Philips’ paper. He presented on the topic, “Ratzinger’s Interculturality and Cardinal Sarah.”Philips remarks about the spirit of the liturgy shared by both theologians. According to Philips, however, there exists a nuance in perspectives between the two theologians. For instance, in the context of appealing to the non-believers, Ratzinger apologetically reverses the axiom of the Enlightenment – “to live by only those truths that would be true even if God did not exist” – to argue that even one who does not belief in God’s existence ought to try to live as though God did indeed exist (velutisi Deus daretur). Robert Cardinal Sarah critiques this, for according to him God cannot simply be a working hypothesis: we live because God exists. Generally, Sarah is weary of a rationalism that denies God or makes him second place. According to him, Africa’s proverbial wisdom is more theocentric and better than the ‘enlightenment’ that denies God. Quoting from Paul VI he affirms that Africa is the new home of the Church/faith for the world.

Despite the progress made thus far by African theologians, Aaron Pidel’s presentation, “Cross-Cultural Biblical Ethics: Ratzinger on the Indissolubility of Marriage”offers a challenge to African theologians, to more generously engage the bible in the process of contextualization in African Theology. Ratzinger’s cross-cultural hermeneutics, he argues, shines a light on how this can be accomplished. Referencing Ratzinger’s response to the text Farewell to the Devil and other texts, he articulates the following principles of Ratzingerian cross-cultural exegesis: pay attention to the culturally conditioned aspects and those that transcend culture, the intertestamental approach, relevance to faith experience, and compatibility with reason. Applying these to the question of divorce and remarriage in the Gospels (Mk 10:1-12; Mt 19:3-12; Mt 5:31-32; Luke 16:18) he demonstrates Ratzinger’s stance on the indissolubility of marriage. Monogamy, for Ratzinger is a fulfilled realization of Christ’s covenantal/spousal relation to the Church.

III. Conclusion

The converging tendency in all the presentations is that of seeking common grounds of dialogue between Ratzinger’s theology and aspects of the African culture in general and African theology specifically. In these endeavours, I find as recurrent theme,the Christ factor. Mathematically, a factor is that number in terms of which another number can be perfectly expressed, without a remainder. In Balthazarian terminology – referenced above by Emery de Gaal, and echoed in Odozor’s keynote address – this amounts to Christ as the universale concretum et personale. All the authors present Christ as he in whom the African culture (and culture in general) and its aspirations reaches fulfilment and perfection. The subject of Christ is therefore the commonfactor in terms of which both African theology and culture come into dialogue with Ratzinger’s theology, in the search for a synthesis of meaning. The goal of this synthesis is to make the Gospel intelligible and meaningful in the given context of concern, as the above papers clearly demonstrated: Christ’s revelation of God is unique; Christ is at the center of Biblical exegesis; Christ is he who draws us to himself and to one another in the liturgy; Christ gives history a definitive direction, hence our confidence in history as salvific; Christthe incarnate and crucified Lord is the personification of solidarity par excellence; Christ is the goal and center of all cultures; Christ’s revolution of love is central to evangelization; Christ (as God) is ground for our existence; Christ, not politics or culture or power is the fulfilment of our deepest human aspirations, yet, this same Christ does not cancel out culture but seeks to be incarnated in each and every culture. Making meaning of this incarnation in the African culture/context is the task of the African theologian.

[1] For details on the event and list of participants,check the linkhttps://usml.edu/joseph-ratzinger-and-the-future-of-african-theology/.

[2]Cf. Ray Wheeler, “The Legacy of Shoki Coe,”in International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 26, 2 (April 2002): 77–80.

[3]Lumen Gentium, Dei Verbum, Nostra Aetate, and Gaudium et Spes are chief amongst the texts that affirm this reality.

[4] John Paul II, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Africa(Sept. 14, 1995),no. 63.

[5] Benedict XVI, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Africae Munus(Nov. 19, 2011),no. 136.

[7] See Ratzinger’s Salt of the Earth: The Church at the End of the Millennium- An Interview with Peter Seewald, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press 1997) for a synthetic portrait of Ratzinger the theologian and Benedict XVI the Pope, in his own words. Also see Aidan Nichols, The Thought of Pope Benedict XVI: An Introduction to the Theology of Joseph Ratzinger (New York: Burns & Oates, 2007).

[8]Original sequence of presentation according to names of authors: 1. Paulinus Odozor (keynote address). 2.Paul Adaja. 3. Aaron Pidel, SJ. 4. Mary Reginald Anibueze. 5. Christopher Collins. 6. Tegha A. Nji and Valery Akoh. 7. Emery de Gaal. 8. Dennis Kasule. 9. Joseph Lugalambi. 10. Joseph Ogbonnaya. 11. Jacob Philips. 12. Maurice Ashley Agbaw-Ebai.

(Authored by Tegha Afuhwi Nji)

24, December 2019

World pilgrims flock to Bethlehem for Christmas celebrations 0

Christian pilgrims from around the world have gathered in the occupied West Bank city of Bethlehem to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ, as local Palestinians suffer from decades of Israeli occupation.

Thousands of Palestinians and foreigners began converging early Tuesday morning on the “little town” in Bethlehem, as the traditional birthplace of Jesus Christ, to hold Christmas Eve festivities in and around the Church of the Nativity.

Archbishop Pierbattista Pizzaballa, apostolic administrator of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem and the most senior Roman Catholic official in the Middle East, who traveled from the holy city to Bethlehem, is scheduled to lead midnight mass at the church in the presence of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

Pizzaballa said although it was a difficult time, there was reason for “hope.”

“We see in this period the weakness of politics, enormous economic problems, unemployment, problems in families — so when we look at this reality, we could say that there is nothing to hope for,” he said.

“On the other side, when I visit families, parishes, communities, I see a lot of commitment… for the future. Christmas is for us to celebrate the hope,” he added.

Rula Maaya, Minister of Tourism and Antiquities of the Palestinian Authority, said the number of foreign tourists visiting the West Bank increased from three million in 2018 to 3.5 million in 2019.

She added that at least 15,000 pilgrims were staying overnight in Bethlehem for Christmas, adding, “All hotels in the city are full today.”

Tourists queued in the morning to visit the grotto inside the Church of the Nativity, believed to be the exact site where Jesus was born.

Fewer Christians from the Gaza Strip were in attendance due to the Israel regime’s restrictions on issuing permits.

Israel granted permits to just around 200 of the roughly 900 people who applied, Wadie Abunassar, an adviser to church leaders in the Holy Land, told the AFP.

Bethlehem is close to Jerusalem al-Quds, but cut off from the holy city by Israel’s separation wall. Israel began building the barrier in 2002 which runs through the West Bank, separating Israeli Jews from Palestinian Christians and Muslims.

Source: Presstv