26, December 2021

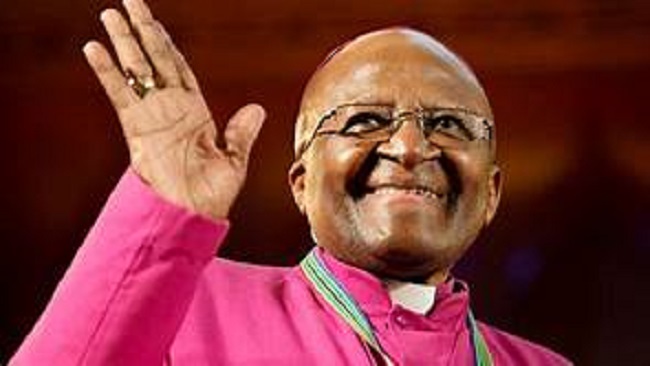

South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu dies at 90 0

South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died Sunday at the age of 90, was the moral compass of his beloved “Rainbow Nation”, never afraid to speak truth to power, whatever its creed or colour.

A tireless activist, he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for combatting white minority rule in his country.

“The passing of Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans who have bequeathed us a liberated South Africa,” President Cyril Ramaphosa said in a statement.

Famously outspoken, even after the fall of the racist apartheid regime, Tutu never shied away from confronting South Africa’s shortcomings or injustices.

“It’s a great privilege, it’s a great honour that people think that maybe your name can make a small difference,” he told AFP shortly before his 80th birthday in 2011.

Whether taking on his church over gay rights, lobbying for Palestinian statehood or calling out South Africa’s ruling African National Congress on corruption, his high-profile campaigns were thorny and often unwelcome.

None at the top were spared — not even his close friend, late president Nelson Mandela, with whom Tutu sparred in 1994 over what he called the ANC’s “gravy train mentality”.

Yet “the Arch” brought an exuberant playfulness to all his endeavours.

Quick to crack jokes — often at his own expense — he was always ready to dance and laugh uproariously with an infectious cackle that became his trademark.

It was Tutu who coined and popularised the term “Rainbow Nation” to describe South Africa when Mandela became president.

At the time, Tutu was serving as the first black Anglican archbishop of Cape Town.

Ordained at the age of 30 and appointed archbishop in 1986, he used his position to advocate for international sanctions against apartheid, and later to lobby for rights globally.

‘Moral titan’

Along the way, he won a host of admirers.

“I believe that God is waiting for the archbishop. He is waiting to welcome Desmond Tutu with open arms,” said Mandela, who stayed at Tutu’s home on his first night of freedom in 1990, after 27 years in apartheid jails.

“If Desmond gets to heaven and is denied entry, then none of the rest of us will get in!”

The Dalai Lama called Tutu his “spiritual older brother”.

Irish activist and pop star Bob Geldof praised him as “a complete pain in the arse” for those in power, and US President Barack Obama hailed him as “a moral titan”.

Among Tutu’s critics were Zimbabwe’s veteran former president Robert Mugabe, who described him as an “evil and embittered little bishop”.

Even with his global celebrity, his faith remained an integral part of his life.

His family’s road trips included quiet time for prayers, and his missives blasting the evils of apartheid were signed off with “God bless you”.

“I developed tremendous respect for his fearlessness. It wasn’t fearlessness of a wild kind. It was fearlessness anchored in his deep faith in God,” said apartheid’s last leader, F.W. de Klerk.

Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997 and underwent repeated treatment.

He had retired a year earlier to lead a harrowing journey into South Africa’s brutal past, as head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

For 30 months, the commission lifted the lid on the horrors of apartheid.

Tutu, with his instinctive humanity, broke down and sobbed at one of its first hearings.

A recipient of numerous awards, his causes ranged from child marriage to Tibet to calls for Western leaders to be tried over the Iraq war, and in later years for the right-to-die.

He also swore he would never worship a homophobic God.

“I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say sorry, I mean I would much rather go to the other place,” he said.

Post-apartheid frustrations

Born in the small town of Klerksdorp, west of Johannesburg, on October 7, 1931, Tutu was the son of a domestic worker and a school teacher.

Following in his father’s footsteps, he trained as a teacher before anger at the inferior education system set up for black children prompted him to become a priest.

He lived for a while in Britain, where, he recalled, he would needlessly ask for directions just to be called “Sir” by a white policeman.

Tutu believed firmly in the reconciliation of black and white South Africans.

“I am walking on clouds. It is an incredible feeling, like falling in love. We South Africans are going to be the Rainbow People of the world,” he said in 1994.

But post-apartheid South Africa increasingly became a source of his despair, as the high hopes of the early days of democracy gave way to disillusionment over violence, inequality and graft.

Never a member of the ANC, Tutu said in 2013 that he would no longer vote for the party, though President Cyril Ramaphosa — an old friend — re-built bridges after coming to power in 2018.

Tutu made a rare public appearance in May 2021 to receive his vaccine for Covid-19. He appeared outside of hospital in a wheelchair, and waved but did not speak.

He married his wife Leah in 1955. They had four children.

Source: AFP

20, January 2022

Former pope Benedict under scrutiny in German child sex abuse investigation 0

A potentially explosive report into the handling of child sex abuse in the Catholic Church will on Thursday be published in Germany, with former pope Benedict XVI among those in the spotlight.

The report by law firm Westpfahl Spilker Wastl (WSW) will analyse how abuse cases were dealt with in the archdiocese of Munich and Freising between 1945 and 2019.

The Munich archdiocese, which commissioned the report, said it will examine “whether those responsible complied with legal requirements… and acted appropriately in dealing with suspected cases and possible perpetrators”.

Ex-pope Benedict — whose civilian name is Josef Ratzinger — was the archbishop of Munich from 1977 to 1982.

During this time, a now notorious paedophile priest named Peter Hullermann was transferred to Munich from Essen in western Germany where he had been accused of abusing an 11-year-old boy.

Hullermann was reassigned to pastoral duties despite his history.

In 1986, by which time Ratzinger had been transferred to the Vatican, he was convicted of molesting more children and given a suspended prison sentence.

Even after the conviction, he continued to work with children for many years and his case is regarded as a pertinent example of the mishandling of abuse by the Church.

Benedict has denied knowing about the priest’s history.

82-page statement

The ex-pope has provided an 82-page statement in response to questions from WSW, according to German media reports.

The pope emeritus “takes the fates of the abuse victims very much to heart” and is fully “in favour of the publication of the Munich report”, his spokesman Georg Gaenswein told the Bild daily.

Benedict, 94, in 2013 became the first pope ever to step down from the role in 600 years and now lives a secluded life in a former convent inside the grounds of the Vatican.

The reformist Catholic group “Wir sind Kirche” (We are Church) called on the ex-pontiff to take responsibility for what happened while he was in charge of the Munich diocese.

“An admission by Ratzinger that through his actions or inactions, knowledge or ignorance, he was personally and professionally complicit in the suffering of many young people would be… an example for many other bishops and responsible persons,” it said in a statement.

Germany’s Catholic Church has been rocked by a string of reports in recent years that have exposed widespread abuse of children by clergymen.

A study commissioned by the German Bishops’ Conference in 2018 concluded that 1,670 clergymen in the country had committed some form of sexual attack against 3,677 minors between 1946 and 2014.

‘Systemic failure’

However, the real number of victims is thought to be much higher.

Another report published last year exposed the scope of abuse committed by priests in Germany’s top diocese of Cologne.

Cardinal Reinhard Marx, the current archbishop of Munich and Freising, last year offered Pope Francis his resignation over the church’s “institutional and systemic failure” in its handling of child sex abuse scandals.

However, Pope Francis rejected his offer, urging the cardinal known for his reforms to stay and help shape change in the Catholic Church.

As archbishop in Munich since 2007, Marx could also find himself under scrutiny in the WSW report.

Friedrich Wetter, who held the role from 1982 to 2007, is also still alive.

The abuse scandal has thwarted the Catholic Church’s efforts to spearhead broad reforms in Germany.

It counted 22.2 million members in 2020 and is still the largest religion in the country, but the number is 2.5 million fewer than in 2010 when the first major wave of paedophile abuse cases came to light.

Payouts for victims of abuse were increased in 2020 to up to 50,000 euros ($56,700), from around 5,000 euros previously, but campaigners say the sum is still inadequate.

Ahead of the publication of the Munich report, the Eckiger Tisch victims’ group called for “compensation instead of hollow words”.

“Far too many children and young people have fallen victim” to a system “shaped by abuse of power, intransparency and despotism”, said Matthias Katsch, a spokesman for the group.

Source: AFP