Categories

Recent Posts

- Football: Panthère du Ndé Wins Cameroon Cup 2025

- Fifa brings in new £45 ticket for 2026 World Cup

- President Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, top aides to appear before the Supreme Court

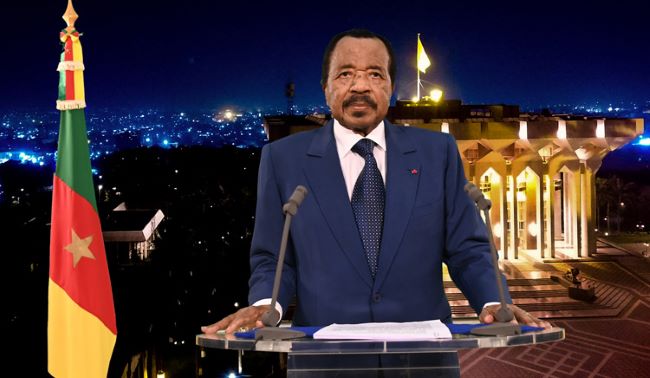

- Pressure mounts on Biya as speculation grows over possible replacement of Ngute

- 2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

Archives

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification  Young Cameroonians: Build social capital to succeed

Young Cameroonians: Build social capital to succeed  Eulogy for HRH Nfor Professor Teddy Ako of Ossing

Eulogy for HRH Nfor Professor Teddy Ako of Ossing  Will Fr. Paul Verdzekov recognize the refurbished and rededicated Cathedral in Bamenda were he to return today?

Will Fr. Paul Verdzekov recognize the refurbished and rededicated Cathedral in Bamenda were he to return today?  Cameroon apparently under a de facto federalism

Cameroon apparently under a de facto federalism

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

18 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

Football: Panthère du Ndé Wins Cameroon Cup 2025

-

Fifa brings in new £45 ticket for 2026 World Cup

-

President Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, top aides to appear before the Supreme Court

-

Pressure mounts on Biya as speculation grows over possible replacement of Ngute

-

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

-

Armed Mbororo tribesmen killed 8 in Southern Cameroons’ new war

-

Southern Cameroons Crisis: Atanga Nji Boys abduct 8 people en route to Kumbo

© Cameroon Concord News 2025

22, September 2024

So, this is why journalists are still doing this largely thankless job? 0

There is an art to surviving disappointment, but you wouldn’t know it from consuming the arts and culture of the Twenties.

We seem to be hostages of an era of corrosive optimism which is allergic to complexity and intellect, and disappointment too.

The prophet Orwell warned us about this type of society and its dangerous simplicities.

In the political sphere, thoughtful critique and debate were once valued as markers of a healthy society. Now we are left with thin-skinned governments and a tendency towards sociopathic leadership all over the world.

Capitalist media owners have contributed by dropping standards for news, stranding us all in a weird space where any mention of real problems on the part of citizens is seen as an attack on government.

In the worst cases, criticism is framed by the powers that be as a form of treachery.

And yet, people still practise journalism in such an environment. What’s going on here?

I remember my first impression of real-life journalists; it was not very good. They’re nothing like the heroes in the movies, I thought, observing their sharp gazes and reticent tongues.

Why aren’t they out there saving the world with their flaming prose of social justice! What a grim bunch of cynics, I thought. I will never become like that, I thought.

I had no idea of what it takes to persevere in a profession that is utterly idealistic at its core. It turns out that journalists are a case study in how to cope with disappointment not only in one’s individual life— it’s a tough gig— but also in society as a whole.

Well. Journalists and Socialists, actually, and here I am aspiring to be one or possibly both when I grow up.

This past week I have been relying on what I have learned over time from the wisdom of journalists and the interminable motivation of modern-day socialists.

Comments made by my Head of State in response to the killing of the Chadema politician Ali Kibao during a celebration of the police were unexpected, bracing.

It was giving ‘Je suis l’etat.’ It was an unapologetic reminder that the state has the monopoly on the means of violence, and it will justify using it… against civilians.

It is now time to sit back, exhale and begin the process of embracing the massive disappointment of having invested support and belief in the current iteration of the government of Tanzania, only to discover that it was old ghosts in newly tailored Ujamaa kitenges. Old threats in new speeches. I know I am not alone at this crossroads.

The sharp gazes and reticent tongues of journalists now look like resilience to me. After all they are still doing this largely thankless job.

Veterans and old socialists have a stoic patience and deliciously dark sense of humour that quietly teaches.

This is what it looks like to survive the death of your hopes and dreams for your country. I don’t know why knowing this is therapeutic, but it is, so I am sharing it here.

There is an art to surviving disappointment. It consists of indomitable— even defiant — optimism and comes with a sharp gaze and reticent tongue.

Tomorrow — maybe next week or next year, it needs time— this too shall pass and hope will come again.

Culled from The East African