Categories

Recent Posts

- Football: Panthère du Ndé Wins Cameroon Cup 2025

- Fifa brings in new £45 ticket for 2026 World Cup

- President Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, top aides to appear before the Supreme Court

- Pressure mounts on Biya as speculation grows over possible replacement of Ngute

- 2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

Archives

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

Featured

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification  Young Cameroonians: Build social capital to succeed

Young Cameroonians: Build social capital to succeed  Eulogy for HRH Nfor Professor Teddy Ako of Ossing

Eulogy for HRH Nfor Professor Teddy Ako of Ossing  Will Fr. Paul Verdzekov recognize the refurbished and rededicated Cathedral in Bamenda were he to return today?

Will Fr. Paul Verdzekov recognize the refurbished and rededicated Cathedral in Bamenda were he to return today?  Cameroon apparently under a de facto federalism

Cameroon apparently under a de facto federalism

Most Commented Posts

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

4 Anglophone detainees killed in Yaounde

18 comments Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

Chantal Biya says she will return to Cameroon if General Ivo Yenwo, Martin Belinga Eboutou and Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh are sacked

13 comments The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

The Anglophone Problem – When Facts don’t Lie

12 comments Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

Anglophone Nationalism: Barrister Eyambe says “hidden plans are at work”

12 comments Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

Largest wave of arrest by BIR in Bamenda

10 comments

Latest Tweets

Featured

-

Football: Panthère du Ndé Wins Cameroon Cup 2025

-

Fifa brings in new £45 ticket for 2026 World Cup

-

President Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, top aides to appear before the Supreme Court

-

Pressure mounts on Biya as speculation grows over possible replacement of Ngute

-

2025 is the year when Biya’s long rule finally lost its last convincing justification

-

Armed Mbororo tribesmen killed 8 in Southern Cameroons’ new war

-

Southern Cameroons Crisis: Atanga Nji Boys abduct 8 people en route to Kumbo

© Cameroon Concord News 2025

24, December 2019

Southern Cameroons special status – too little, too late? 0

Cameroon’s English-speaking MPs have reacted angrily to the new bill, that if signed could grant a ‘special status to Cameroon’s two crisis-hit Anglophone regions, which was passed by lawmakers of the lower house on Wednesday. The bill is an attempt to resolve a three-year conflict in the English-speaking regions that has left at least 3,000 people dead and around 600,000 people displaced, according to the International Crisis Group estimates.

If the Senate approves the devolution law and it comes into force, Cameroon’s Anglophone Northwest and Southwest Regions, where separatists are fighting government troops , will be able to develop their own education and justice policies. Decades of resentment at perceived discrimination against a fifth of the population in an overwhelming French-speaking country have boiled over into an armed campaign for independence that has been met with a brutal crackdown in 2017.

The proposals

The bill contemplates the creation of assemblies of chiefs, regional assemblies, and councils, with each of the two regions having elected presidents, vice presidents, secretaries, and public affairs management controllers. Three commissioners will be responsible for “economic, health, social, educational, sports, and cultural development affairs”. Additionally, independent public conciliators will be put in place to solve disputes over the functioning of regional administrations. The bill also proposes more powers for elected mayors to recruit hospital staff and teachers.

However, all of this is not enough, says Dr. Nick Ngwanyam, a politician who grew up in the Anglophone region. “When we were told that we would have a special status, everybody was confused. It was something we were not really looking at. In terms of terminology, we had to find out what it meant. It was like an empty container and everybody was waiting for the meaning to fill it. And when that meaning came, I for one realized it would not solve our problems.”

“Too little, too late?”

“It is too little, coming too late”, says Senator Henry Kemende. It says in Section 328: In addition to the powers devolved on regions by the proposed law, the North-West and South-West Regions may exercise the following powers: Participating in the formulation of national public policies relating to the Anglophone education sub-subsystem. This is like a piece of sugar in a basin of water, their participation will not be felt. What we would have expected is to empower the regions to determine policies over the educational, judicial, legislative and executive system, to determine issues at a national level, and not just a local level”, Kemende emphasizes.

The power to address issues that directly affect their daily lives is what Anglophone’s have been yearning for in Cameroon’s Northwest and Southwest regions, Kemende told DW in an Interview. “They are the people who want to be in control of their own destiny, without guidance from somewhere else with foreign mindsets that don’t suit their local realities.”

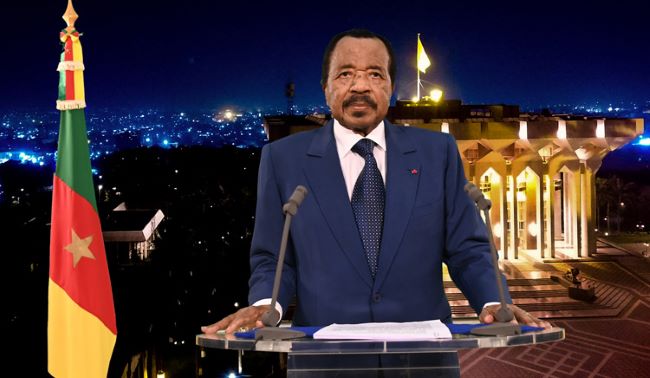

In October, President Paul Biya’s government held a “major national dialogue” to settle the Anglophone crisis

Special status: No novelty

After all, the idea of special status is nothing new, says the senator. “It is no novelty before we joined then La Republique Cameroun, Cameroon had a central government that gave the Anglophone regions a special status and a state, but they consulted the people. This time now, they are going back to the special status that they have enjoyed before, but why did they not consult the people concerned?”

Some MPs from the ruling party expressed their anger as they could not make recommendations or make amends to the bill. Questor Cyprian Awudu Mbaya, asked the minister of decentralization in parliament, “why didn’t you just take the text and the president would have just signed a decree? We cannot change even a comma because you will defend it.”

According to 63-year-old Ngwanyam, the government has not taken the tools necessary to bring a long-lasting solution on the table. “If you have a piece of meat and you want to cut it, you use a knife. A knife has a sharp and a blunt end, and using the blunt one would take a lot of time. Why don’t we use the tools that work?”

Unity of a federation – Cameroon is struggling to find a long-lasting solution

The fear of federation

The sharp end of the knife – this is what Ngwanyam calls his idea of a federation for the Anglophone regions of the country. He had suggested this solution in September, with the aim of breaking down the country in East and West Cameroon. “The special status was written with the spirit of assimilation, an agenda that Paul Biya has been running on for the last 36 years.” He does not understand why the government fears a federation system of governance. “They should explain it. Then we can begin to find out why a special status would do the trick.”

In October, President Paul Biya’s organized amajor national dialogueto discuss the anglophone crisis, but the main separatist movements boycotted the forum. One of the key recommendations of the talks was more autonomy for the English-speaking regions, which have so far failed to bring peace and had been criticized for lack of legislative follow-up. The United States has since backed the prospect of devolved power in the troubled regions, saying that the government’s military response was only strengthening separatists.