Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

1, March 2020

Southern Cameroons War: The World’s Refugee System Is Broken 0

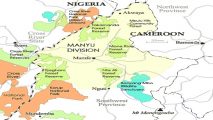

Rose grew up in an English-speaking region of Cameroon, a Central African country uniquely, and violently, divided by language. When she was young, on the instructions of her father, she handed out fliers for a secessionist group opposed to the Francophone-controlled government. But as a teen, after she was sexually assaulted by security forces looking for her father, she swore off politics and became a teacher.

Two decades passed. On a visit to her home village in 2016, Rose attended a protest demanding resources for Anglophone schools. Teachers and lawyers were the tip of the spear of a burgeoning independence movement centered on language. At the demonstration, officers hit Rose on the head with something powerful enough to knock her out and land her in the hospital for months. Afterward she was repeatedly brought in for questioning by police. Her family name, linked to the secessionist movement, made her more of a target. (For this story, she asked to use a pseudonym.)

As she watched other teachers being hauled off and never heard from again, she decided to leave the country. Over the last three years, the violence in Cameroon has led to more than 3,000 deaths and uprooted half a million people—the fastest-growing displacement crisis in Africa, according to the International Rescue Committee. Asylum seekers from Cameroon often go west, to Europe and the United States. But Rose’s broker, whom she paid nearly $7,000, surprised her with the news that he could get her a visa to Japan, a country she knew almost nothing about. She had little idea of what she would do with her life when she arrived there, and barely 24 hours to decide. Still, she told me, “I just wanted to be in a safe place.”

The leaders who created international refugee policy never envisioned people like Rose, a middle-class 39-year-old woman desperate for safety from a conflict the rest of the world isn’t paying attention to. Violent flash points rooted in all kinds of new phenomena—police corruption, climate change, gang warfare—now dot the Earth, creating the conditions for the worst protracted migration crisis since World War II. The pull to more stable corners of the planet is more potent now, too, given social-media postings from cousins and friends abroad who amplify (and often inflate) newfound opportunity. And given relatively affordable airline travel, plus the ubiquity of smartphones—which ease language, navigation, and homesickness challenges—moving is logistically easier now. This has all turned Japan into an unlikely destination for asylum seekers.

The problem is that the refugee system set forth in United Nations documents signed by most of the world’s countries, including Japan and the United States, does not apply to Rose—at least not how it is currently enforced. The 1951 and 1967 agreements were drafted to specifically address European displacement from World War II while more broadly setting rules to protect people from persecution going forward: Anyone who is “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

But persecution is in the eye of the beholder, with interpretations of “unable or unwilling” varying based on the country of resettlement, the political party in power in that country, and the individual bureaucrat reading the application. To get refugee status and a pathway to permanent residency, asylum seekers generally must prove that they were personally targeted by documenting their persecution with paperwork—ostensibly from the very same authorities they are fleeing from. They are eyed suspiciously as mere economic migrants; poverty and hunger, though defining features of persecution, are not accepted reasons for being granted asylum.

We are in an age of mass displacement. Yet the powerful and stable nations of the world have not figured out a humane way to handle the influx of people claiming persecution while balancing domestic concerns about security and cultural change. Instead, doors are simply closing, with asylum protections rolled back seemingly everywhere. In Italy, where the former interior minister denounced “fake refugees,” boats of Africans have been blocked from docking. The European Union pays handsomely to keep asylum seekers away, while Turkey considers sending Syrian refugees back to their homeland, which is still at war. In the U.S., the indefinite detention of asylum-seeking children prompted the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to say she was appalled. Thousands of asylum seekers are sent from the U.S. to dangerous sections of Mexico and even to countries they’re not from.

Cameroon’s problems may have not attracted international attention, but its people are showing up around the world, including at the U.S.-Mexico border; Rose has a brother in South Korea and a son, who also fled for safety, in Minnesota, living with an uncle. On her layover to Tokyo, someone sent Rose a WhatsApp message with a number for a Cameroonian woman in Japan.

Rose didn’t ask for asylum at Narita International Airport in Tokyo, which would have likely gotten her locked up in a detention center. Hunger strikes in Japan over poor conditions for detainees are common, just like in the U.S. Instead, Rose entered Japan on a tourist visa and was lucky enough to find an English-speaking Japanese man who drove her around until she found a hotel room she could afford. She then connected with her compatriot in Japan, who told her about the Japan Association for Refugees, a nongovernmental organization that assists asylum seekers, where she met with a case worker.

“He said, ‘Your case will never be approved,’” Rose recalled. “And I was like, ‘Is this man okay?’” She has a 20-stitch scar stretching from her hairline clear across the side of her skull, and surely Japanese authorities, like the rest of the world, knew about the carnage in Cameroon. “I was shocked. I was speechless. And I was very, very disappointed.”

Japan received 19,629 applications for refugee status in 2017; 20 people were accepted. The following year, just 42 people were admitted. The rate at which Japan accepts such applications is the lowest in the G7. Yuki Tamura, a deputy director at the Japanese Foreign Ministry, said in an interview that the number of resettled refugees preapproved to move to Japan via the UN refugee agency will soon increase, from 30 to 60. (That compares to 30,000 last year in the U.S., though this cap has been lowered to 18,000 for this year.) He also defended the low number of asylum seekers who arrive in Japan without prior permission and then win refugee status, as Rose is trying to do. “Japan’s decision to accept or not accept asylum seekers is not politically inclined. We accept refugees after assessing the situation based on domestic laws,” he told me.

Domestic laws, of course, don’t reflect the kind of refugee the world is creating. Climate change is expected to displace at least 25 million people by 2050, while sexual violence and gang extortion in Central America are forcing migration to the U.S. and even Europe, yet there’s no international standard on how to deal with such victims. The Obama administration granted asylum to credible cases involving gangs, but that was reversed under President Trump. In Europe, Belgium recognizes gang violence as a legitimate refugee claim, but Spain doesn’t.

The irony, says David Slater, an American anthropology professor at Tokyo’s Sophia University who works with asylum seekers in Japan, is that those who appear to have the most straightforward cases of persecution “are the ones who are least likely to have documentation” to prove that it happened. “You don’t stop off at the local police station, especially when the police are part of the people who are persecuting you, to try to get a police report,” he said. (Rose, for example, fled in a rush with two small bags.)

Slater is collecting oral histories from asylum seekers, and he told me he has often wondered, “How can I possibly determine the accuracy or the legitimacy of this claim? It’s not possible.” Governments can no longer distinguish between “an economic migrant seeking to better his or her life and a refugee who is just trying to survive,” he says, because “everybody has a little bit of both in them.”

And yet that’s exactly what asylum and refugee officers are tasked with doing. “I would say that the system is broken,” Slater says. “The amount of conflict in the world and the number of people who are fleeing are so disproportionately larger now. For us to try to use a framework that was designed under a particular set of conditions and under a particular scale is no longer feasible.”

When Rose eventually gets an interview with a refugee officer, inconsistencies in her story—or confusion in the translation—could lead to allegations of fraud and deportation. Rose doesn’t even remember the precise date of the 2016 protest she was involved in, and she hasn’t been able to obtain her hospital records documenting her injuries.

Japan’s low birth rate and undermanned workforce indicate a need for immigrants. But assimilation is viewed as a barrier. Just 18 percent of Japanese, the lowest of any country surveyed in a 2016 Ipsos poll, think refugees could successfully integrate into their country. A myth persists that the Japanese are of a single bloodline connected to the emperor, and that view affects refugee policy, according to Osamu Arakaki, a professor at International Christian University in Japan and an expert in Japanese refugee law. He told me that the common blood is seen as “energy for the successful economic development in the 1970s and 1980s,” and therefore homogeneity is necessary in order to “maintain ethnic and economic harmony.”

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe warned in 2014 that “in countries that have accepted immigration, there has been a lot of friction, a lot of unhappiness both for the newcomers and the people who already lived there.” So Abe’s policy is to instead direct money to the UN refugee agency. Though its contributions have been declining in recent years, Japan remains one of its most generous state donors, supporting the displaced who are temporarily living in refugee camps. Yet that money only goes so far; the agency is 57 percent underfunded overall.

The world’s most neglected displacement crisis, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council, is in Cameroon. In 2018, there were 203 applications for asylum from there in Japan and no approvals, according to UN data. Other groups have a similarly hard time: Tokyo has given refugee status to just one person claiming persecution due to sexual orientation, and no Kurds seeking asylum from Turkey, despite thousands of applicants. Syrian refugees have had particular trouble winning asylum, although a handful have been admitted as students.

Rose has been hospitalized in Tokyo due to her head injury, and she faces poverty, eating just rice most days. And like refugees everywhere, she suffers from the trauma of family separation.

Rose longs for her family, her career, her old life. She worries about her chances at refugee status. But she retains a degree of optimism. “The fact that I’m living in a safe country where I’m not afraid of rape at any time, or gunshots, give me some sort of hope, some assurance, that some things will change for me,” she says. “I’ve never been a refugee before now, so I really don’t know how it works. But I just hope it works well for me. I don’t know how, but I hope it works well.”

Source: The Atlantic.Com