Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

3, March 2020

Battle for the Federal Republic of Ambazonia: An unravelling catastrophe 0

The day the military came to Bella’s village in Talingai, in the South-West Anglophone region of Cameroon, the villagers, terrified, escaped into the bush behind the village, where they set up a camp. Speaking to RFI in Mamfe, smartly dressed in a bright blue dress, it is only when she begins her story that her whole body heaves, her shoulders hunch up. She distinctly remembers what happened this time last year, that changed her life forever.

Bella was nursing her second child and sneaked back during the day to pick up some supplies from the house. She spent the night at home after it got too dark to leave. When she returned to the bush, her pregnant sister-in-law and four young children were nowhere to be found. She searched for them for four days.

According to Anglophones RFI spoke to for this article, people are scared, threatened and some have been tortured by the Cameroonian military and rebels, their homes burnt down by men in uniform or had friends and family killed in the fighting between security forces and Anglophone separatists.

The UN sounded the alarm in February, when they confirmed through sources on the ground that armed men carried out the extra judicial killings of at least 21 people in Ngarbuh, the North-West region of Cameroon, including a pregnant woman and seven children, in addition to other reports of military action against civilians in that area.

French President Emmanuel Macron acknowledged the “deteriorating situation” in the Anglophone regions days after the attack, and came through on his promise on Sunday to call his Cameroonian counterpart Paul Biya to apply “maximum pressure”, calling the violence “intolerable.”

Both Macron and Biya “agreed an impartial probe was needed in reaction to the violence committed against civilians in the village of Ngarbuh in the North-West province,” according to the statement released by the French presidency.

Human Rights Watch has since accused the Cameroonian military of carrying out the killings in Ngarbuh, with the help of Fulani fighters.

Cameroon’s Defence Ministry initially said on 17 February the government would open an investigation into the killings. It published a second statement later the same day that fighting against “armed terrorists” who attacked government and security forces led to the explosion of fuel containers, resulting in the deaths and burnt homes. Communication Minister René Emmanuel Sadi reiterated that statement the next day.

An assessment carried out by the UN in September 2019 shows more than 700,000 people have been forced to flee their homes in the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon, a number considered to be a significant underestimate as access to the area has been difficult.

Violence began in 2017 in both the North-West and South-West regions in the aftermath of peaceful protests by Anglophone teachers and lawyers who took to the streets to demonstrate against alleged discrimination and unfair working practices enforced by the Francophone central government.

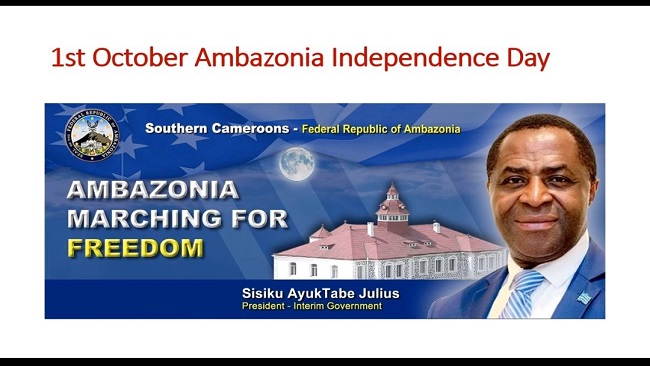

The ensuing government crackdown since then provoked the creation of an armed separatist movement and self-declaration of independence for so-called Ambazonia. The separatists are fighting for Anglophone secession.

The crisis in the Anglophone regions has swelled into an all-out civil war fought by the Ambazonians, colloquially called Amba Boys or Ambas, made up of a number of different armed groups. The Anglophone rebels are fighting the Cameroonian military, specifically the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR), the elite fighting unit accused of human rights abuses in the far north of the country.

Changing strategy and intimidation

The Cameroonian military’s tactics of targeting the Ambas have evolved during the crisis and recently soldiers have attempted to change their approach with the local population, according to Anthony, a resident of Sand Pit, a neighborhood in Buea.

He recounted how two weeks ago, the military travelled in a yellow taxi into Sand Pit in full uniform with weapons. He guessed that they were trying to trick the population. They caught five people and started beating them with cutlasses, he says. Those people now have wounds on their backs.

“Then they put the Pa on the ground,” he says, using a respectful term for an older male member of the community, “and they put the gun next to the ear of the Pa, and they shoot the gun right next to him,” he says.

The older man has been plagued with hearing problems ever since, says Anthony, who was displaced by the fighting three months ago. He shakes his head as he speaks of how the military intimidated the Pa and others in the community.

The story Gabriella, 32, tells is an example of how the killings in her family cross both sides of the conflict. Speaking in Mamfe town, she had not told her story to anyone outside her family before, in part, she says, because everyone else around her is suffering, but also because she trusts no one.

The military came to Mbeme village two years ago, hunting Amba Boy separatists who operate in the area. Spraying bullets among the dried mud houses in the village, one stray bullet killed Gabriella’s husband. Two weeks later, her 15-year-old son, the eldest of seven, was gunned down in the barber shop in the village, a victim of being young, Anglophone, and male.

Her father, a village elder, had questioned why the Amba Boys were shutting down public schools, and pushed for the children of the village to go back to school.

The separatists have blocked the opening of some 4,500 schools across the region for more than three years to protest what they call educational discrimination against Anglophones. To date, this boycott enforced by the gun has affected 600,000 schoolchildren.

A week after his grandson died, the Amba Boys came knocking on his door at night.

“They shot him. It was a premeditated act,” said Gabriella, the tone of her voice rising as she confirmed she had lost three male members of her family in the span of a month. She has been bottling up this story and only now feels ready to share the description of the atrocities committed in her village by both soldiers and separatists.

Both sides committing violence against civilians

Human rights abuses are being perpetrated by both sides, confirms Ilaria Allegrozzi, senior researcher on Central Africa for Human Rights Watch. She has documented abuses, deaths, and violent acts since the crisis began in late 2016.

“It’s important to acknowledge that human rights violations have been committed by the security forces but at the same time, the separatists are not angels and have also targeted civilians,” she says.

“The gravity, the scale of the abuses that we have documented coming from the security forces are more significant than the abuse that is perpetrated by the armed separatists,” the HRW researcher adds. The abuses are frequently just the start of the nightmare for Anglophones living through the conflict, where their only option is to escape the patrols of soldiers and separatists through their village.

Gabriella says she, her six children and the whole village fled into the bush. Her two cousins died in the jungle, where malaria, lack of shelter, no sanitation, and the absence of running water makes survival difficult.

She brought her remaining family to Mamfe town because she said she could not subject them to the harsh reality in the jungle. In town, she is alone with her children, and she has no relatives to help. She volunteers her cleaning services in the hope that she can beg for some rice for her children.

“I’m finished, I have no talk,” she says in Pidgin English. “Since the crisis, look at me,” motioning at her bedraggled dress. “I’m tired. I don’t have anything to feed the children.” Neither she nor her children have eaten for several days.

RFI spoke to more than 30 internally displaced Anglophones in and around Buea, Kumba, and Mamfe in the South-West Anglophone region of Cameroon.

People spoke primarily of military harassment, from looting and burning homes to shooting civilians, either targeting people or shooting in the air, which has killed a number via stray bullets. They spoke of security forces targeting villages where many lived as subsistence farmers or worked on plantations for the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC), a parastatal company that was the country’s second-largest employer.

Residents in the South-West region say the Cameroonian security forces will torch a home if they see a young man fleeing in the vicinity. Young men are targeted typically because the separatists recruit young Anglophone men to fight against the military.

After constant harassment and killings by soldiers, Pierre, a 38-year-old from Ekona village, had enough. He says he has been targeted by the military because he is a man, and an Anglophone.

“They killed my elder brother first. Then my second brother. Then they killed my uncle,” he says from Buea, the regional capital of South-West Cameroon.

“I can’t stay there after they killed them — I’ll be next,” he says, nervously wringing his hands. Pierre found it difficult to recall the killing of his family members.

Grace, 38, paid the price after one of her male neighbours ran off into the bush where she lived. She was by herself in her home in Maumu village in September 2018 when the military came knocking, demanding to know where her neighbor had gone.

“The military man went and stood at my door. He called me, and then he shot me in both legs,” she says, describing how one of the soldiers escalated the situation without warning.

After neighbours came out of the bush to smuggle her to the hospital, the military searched the local health facilities, looking for her. Hospital staff hid her in a closet.

Grace, crying, says she is afraid they will find her again. She spoke to RFI on the condition that her real name and location would not be revealed. She owes hospital bills of nearly 1,400 euros (900,000 Central African CFA Francs), and is unable to walk. Her left leg is bandaged because she has an open wound from the gunshot that has still not healed, a year and a half after the shooting.

“Civilians have been caught in the middle, and have paid the highest price in this crisis,” says HRW’s Allegrozzi. “People have been displaced, have lost their families, are living in the bush and are in need of humanitarian assistance. And this crisis has yet to be addressed.”

A population terrified

Anglophones feel that the military is given free rein to do whatever they want.

Meanwhile, those villagers whose houses are still standing maintain they are too scared to sleep in their own homes and prefer to sleep in the bush. They return home occasionally to harvest their crops so they can eat. Those who have migrated to towns also venture back to their homes, but only during the daytime, in order to gather more food to eat and sell.

Bella, the young mother who could not find her five relatives, says she was determined to find out where they were. She puts her hands in her lap, her chewed nails betraying her anguish as she tells her story with little emotion.

“I went to town to report them missing, and to see if they were arrested,” says Bella. The military maintained they had not detained her family members, and she would find them in the bush. They even asked her to call them with an update.

While Bella mustered up the courage to speak to the military, most Anglophones RFI met are afraid — afraid of being shot, or disappeared, or afraid that the military will burn their house down, as they did to their neighbours.

Three years into the horror of losing family members, losing jobs, and losing sleep, many Anglophones, who perhaps were initially on the side of their separatist brethren, now distance themselves from the Ambas, both physically and philosophically. Leigh, 66, said she is afraid of both sides.

“Both are dangerous. Yes, I mean the Amba Boys. If you don’t give them money, you will be beaten. They can kill you,” she says.

Before her community relocated to the bush, she said that the Ambas would sometimes warn them with a whistle when the military were coming so that they could run.

“Now they don’t give any sound. Now they are against us, the military are against us, we are the ones suffering. When the army starts shooting they don’t ask who is who, they just shoot,” she says with a sigh, after rapidly recounting her story.

Fear among civil society groups, too

Local non-governmental and international organisations are trying to provide aid to the most vulnerable members of the Anglophone population, however the level of fear is reflected amongst the humanitarian workers too. A number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were afraid to go on the record regarding the difficulties they have in maneuvering through the terrain, and in dealing with the government.

Local aid group Authentique Memorial Educational Foundation (AMEF) was at the forefront when the fighting broke out between the military and the Amba Boys in Kumba town, where they operate. The difficulty lies in both the separatists and the government believing that aid organizations are helping the other side.

“There is that fear you’re being branded a spy,” says Atim Taniform, AMEF humanitarian affairs and operations manager in Kumba, saying that NGOs are working in a fog of uncertainty.

“We are afraid that the [government] administration thinks that we are bringing assistance to non-state actors [separatists] instead of the community. At the same time, the non-state actors feel we are taking assistance from the administration and bringing it to ‘their’ community,” she says, referring to how the Ambas refer to Anglophones. Taniform chooses her words carefully when referring to the parties of the conflict.

Both sides do not understand humanitarian principles and how they are applied in real terms, according to Christian Tanyi, head of the Martin Luther King Jr. Foundation (LUKMEF), a human rights organization that operates out of Buea.

“When you look at humanitarian principles, the principle of neutrality doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk to people. We talk to all parties in the conflict, trying to explain exactly who we are, what we do and how we do it,” says Tanyi, who says he has tried to explain the rules of engagement to both sides.

“The humanitarian situation continues to deteriorate mainly due to multiple displacements as a result of attacks against civilians,” says James Nunan, UN Office of Humanitarian Affairs regional head in Buea, South-West region, Cameroon.

The bottom line, says Tanyi, is the military and the separatists are not respecting international humanitarian law, as humanitarians and vehicles with humanitarian aid have been attacked by both the military and the separatists.

“All these attacks signify that there is still a very long way to go,” he adds.

As of press time, the Cameroonian military had not responded to a request for comment.

‘We are suffering and we just want it to end’

The majority of Anglophones still believe the government could stop this with one phone call from President Paul Biya, as well as pulling the military out of the region, including the 1300 troops and police brought in for February’s elections.

On February 11, Cameroon’s Youth Day, Biya spoke in French dubbed into English, calling for young Anglophones to come out of the bush, a move opposition Senator George Kinyang said was inadequate.

“Who’s going to employ them, willing them to come out of the bush when their houses are being burnt down in the northern South-West region,” said Kinyang from his home in Douala. He says he cannot return to his constituency because of the fighting.

“How do you call people to come out when they’re not sure of their security, when they are not sure of their livelihood, when they have no assurance that their human rights will be respected,” he adds, saying that the only way to end the conflict is a ceasefire, a move that would be welcomed by those who have already suffered enough.

A worried Bella, still looking for her missing family, left the military headquarters in her area and rushed back to the bush camp, where she found a shallow grave. Other members of the community helped her dig it up, where she discovered the bodies of her four young nephews and pregnant sister-in-law.

She called the military, telling them she found the lifeless bodies of her family.

“The military told me they were there to shoot Amba Boys,” she says, recalling the conversation, her voice cracking. “And when they saw they killed civilians, they tried to bury them.”

She said the soldiers apologized to her.

“They gave me 2,000CFA (3 euros) phone credit” to compensate for her losses, she says, laughing bitterly, before her laughs turn to sobs. Her reaction borders on hysteria – such a meagre compensation in phone credit for the killing of her family is unfathomable.

“People have lost their lives and [others] are dying,” says Bella, through a veil of tears. “I want everything to be over.”

*Names have been changed for the safety and security of those featured in this report

Culled from Radio France International